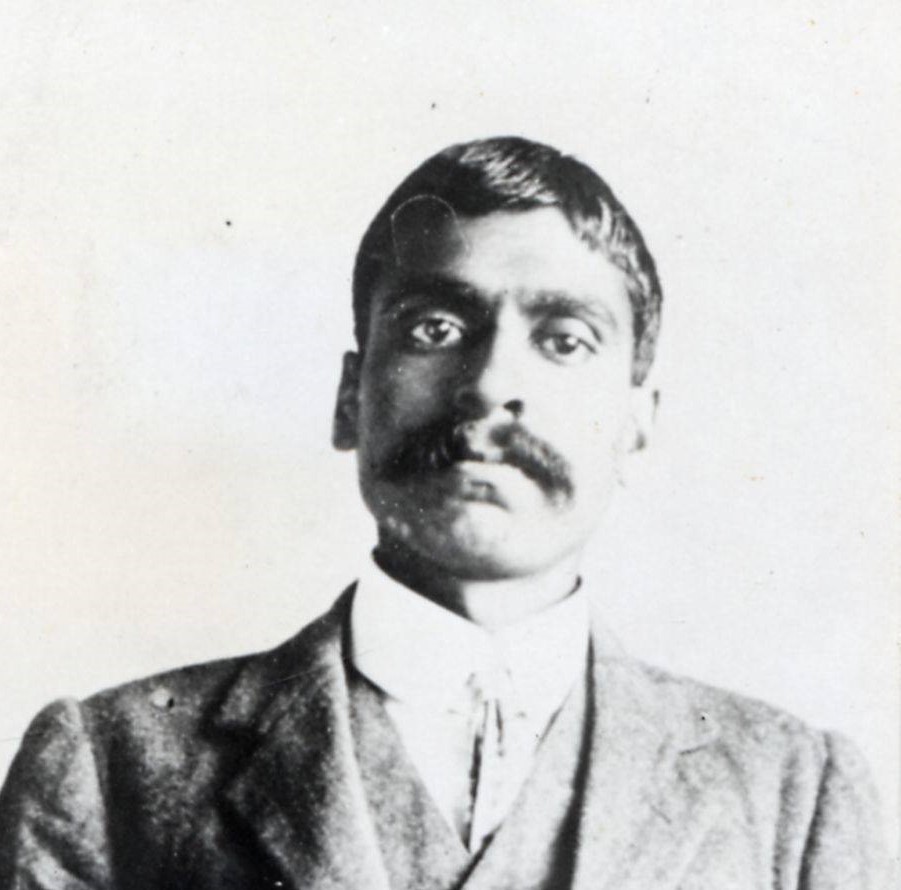

Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur was born on 2 September 1838 in the town of Birnagar, formerly known as Ula or Ulagram, in the Nadia district of West Bengal. Born into a traditional Hindu family of wealthy Bengali landlords, his birth name was Kedarnath Datta. Much of the quoted material in this article is from Bhaktivinoda’s autobiography, which was originally a letter he wrote to his son, Lalita Prashad Das, in answer to some questions about his father’s life.

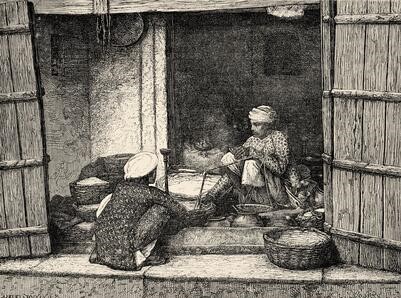

In those days Ula was free from suffering. There were fourteen hundred good brahmana families, and there were many “*kayastha” and “*vaidya” families too. No one in the village went without food. One could get by with very little in those days. Everybody was cheerful – people used to sing, make music, and tell entertaining stories. You could not count how many jolly (fat) bellied brahmanas there were. Almost everybody had a good wit, could talk sweetly and was skilled in making judgments. Everyone was skilled in the fine arts, song and music. Groups of people could be heard at all times making music and singing, playing dice and chess … If anybody was in need they could go to the home of Mushtauphi Mahasaya (his maternal grandfather) and get whatever they required without any difficulty. Medicine, oil and ghee were plentiful … The good people of Ulagram did not know the need of finding work in order to eat. What a happy time it was!”

[*Kayasthas were a community or social group of India. Tradition gives them both brahmana and kshatriya [dual-varna] status. *Vaidyas were traditional Hindu Ayurvedic physicians].

My maternal grandfather had incomparable wealth and a grand estate. There were hundreds of male and female servants. When I was born I had an older brother, Abhayakali, who had previously died, and a second brother, Kaliprasanna, was still living. I was my father’s third son. It was said that of all my brothers I was a little ugly.

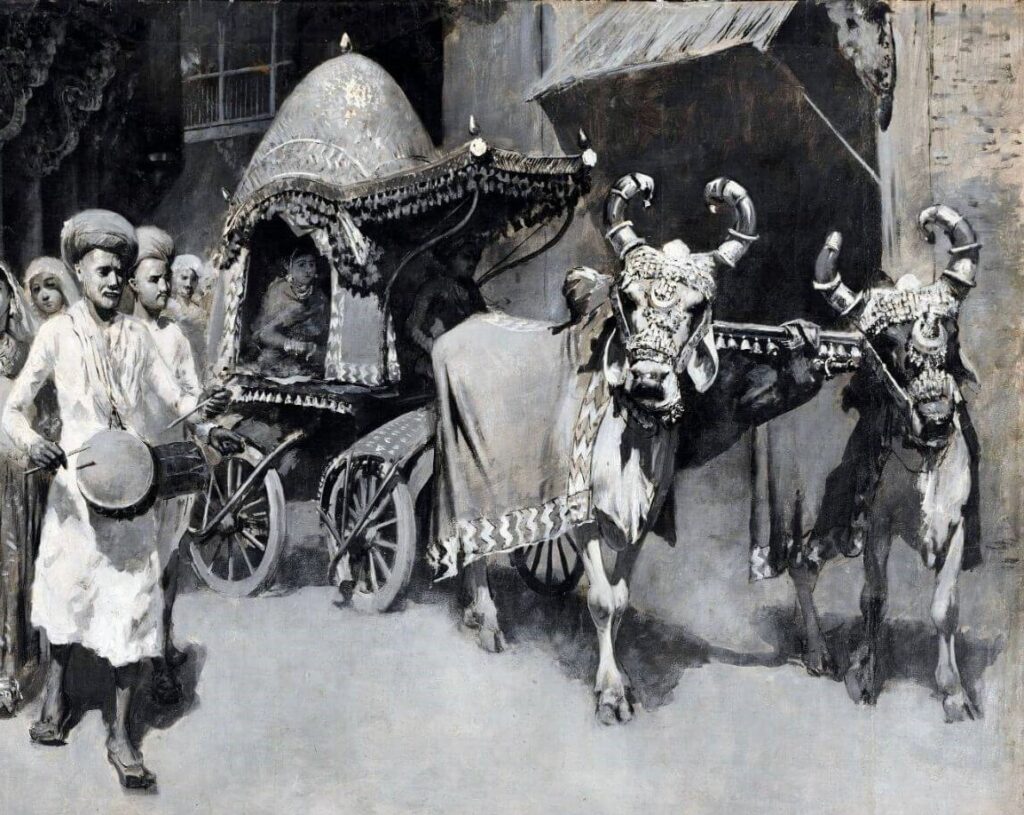

Bhaktivinoda Thakur also had younger brothers, Haridas, and Gauridas who was very beautiful, extremely naughty, and always in trouble. The boys would ride atop their personal elephant named Shivchandra, who would carry them to the places of entertainments during festivals.

Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura recalls the recitation of Mahabharata and Ramayana at the festivals:

When there was recitation of the Mahabharata, Ramayana etc. at the old house I would go to hear. I liked to hear about Hanuman crossing the ocean to Lanka and about the demoness Simhika. The honorable reader would speak with specific accompanying gestures, and in my mind a great love would arise. I would make a regular habit of going to hear the reading after school.

Kedaranatha used to sit and talk with the gatekeepers to avoid getting into difficulty with his naughtier brothers. The soldiers used to tell him stories and recite the Ramayana, to which Kedaranatha was very much attracted, and he began to recite the stories to his mother and maid-servant. His mother was pleased and sent some gifts to the gatekeepers. In return, Srital Teoyari, the main story-teller, would share his rotis (flat breads), dahl (bean soup) and kichari (a combination of dahl and rice) with Kedaranatha, and Kedaranatha would become very happy. These incidents serve to show how Kedaranatha was attracted to hearing about Rama and Krishna from the very beginning of his life, in preference to the playful sports of his brothers.

Sometimes the boy used to wake up at night and talk to the night guards of the inner grounds, particularly one called Officer Naph, who was very old but still used to carry his lantern, stick, club and sword. Officer Naph was a much trusted guard of Kedaranatha’s grandfather. He was fearless, and a former dacoit (robber). Kedaranatha used to ask him many questions. When Naph was a dacoit, he had accidentally beheaded his own guru during a raid. Since that time he had constantly chanted the holy name of Hari. Although only six or seven and incapable of understanding all of Naph’s amazing stories, Kedaranatha liked to hear him talk. Not the least of his attractions must have been the almost constant vibration of the holy name issuing from his mouth.

Then one day, when Thakur Bhaktivinoda was about eight, the boys ate some impure foodstuff. Later that night the Thakur and his elder brother, Kaliprasanna, became ill with cholera. A local doctor declared it very serious and Bhaktivinoda Thakur and Kaliprasanna set out for their home by palanquin.

Kali Dada was sinking gradually into the illness. As we crossed the river Anjana I made a strenuous effort to pacify his mind. By eight o’clock the following morning the palanquin arrived at Ula.

An hour after arriving home, the boy left this world, and a great cry of grief went up from the women of the house.

Bhaktivinoda Thakur’s maternal grandfather gradually fell into debt as a result of numerous expenses and swindlers who took advantage of the elderly gentleman’s generosity. Sivchandra the elephant died and the horse and carriage were sold. Then in his eighth year Srila Bhaktivinoda’s two younger brothers, Haridas and Gauridas, successively died. His mother and father experienced deep grief and suffering on this account. They had lost four of their five sons. That left only Kedaranatha [Srila Bhaktivinoda] and his younger sister, Hemlata. Their nanny went everywhere with Hemlata on her hip and holding the boy by the hand. His mother was so worried that none of her children would survive that she put many talismans around the necks of the children.

Kedaranatha was very attracted to any kind of religious festival or puja that was being performed. If he heard of one, he would arrange to go and see it. He occasionally visited a brahmacari who performed worship according to the doctrine of tantra (sorcery). The brahmacari had cups made from skulls which were kept hidden in a small room in his house.

Some people said that if you gave Ganges water and milk to a skull it would smile. I tried to observe this and thus gave water and milk to a skull, but I saw nothing.

Another person who lived in the same area used to sing devotional songs. During the Durga festivals Kedaranatha would visit the houses of the brahmanas to get prasadam. Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura recalls:

Sometimes, in the hope of getting some nice prasada, I would accept an invitation to eat. In some homes I would get good dahl along with vegetable curry and rice. In other homes I would get kichari and dahl cooked with jackfruit and other things.

On both the paternal and maternal sides of the family, fortunes declined. His paternal grandfather, Rajavallabha Datta’s residence in Orissa was mortgaged and other property was lost. Ananda-candra, Bhaktivinoda Thakur’s father, seeing both the failing fortunes of his father-in-law and father, tried to secure land for his immediate family. He got an opportunity to take managerial responsibility for some property belonging to a friend of his father-in-law, and went to see the land.

In the mean time, Ananda-candra’s step-mother died and he inherited six rent-free villages in Orissa. A family friend set out for Ula to report this news. Two or three days after Ananda-candra’s return to Ula, he came down with severe fever. The best medicines available were administered, but nothing worked. The boy was constantly at his father’s side. One night while he slept, his father gave up his life and was taken to the bank of the Ganges at Santipura. The house was filled with lamentation.

When I rose at dawn I could not see Father. There was no one around. At that time Lalu Chakravati and Paramesvara Mahanti had come from Orissa and they had carried my father to the bank of the Ganges. Seeing everybody crying, I also began to cry. My honorable mother, being in anxiety, was weeping, and many people were trying to console her … Loud sounds of crying filled the house.

Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur was eleven years old at the time of his father’s death. It was a very disturbing time for him with uncertainty in all directions. He continued his studies but his heart was not in it, and he sometimes secretly drank castor oil to make himself sick, so that he wouldn’t have to go to school. Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur recalls:

Even while Father was living I began to become a little thoughtful. ‘What is this world? Who are we?’ These questions were in my mind when I was ten years old. … I would read the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Kali Purana, Annada Mangala etc. from Bengali manuscripts and imbibed much lore in this way. I would discuss these edifying subjects with whomever I met who was a little learned.

One day, when the boy went to eat star-apples in the garden near the parlor of his grandfather, he became frightened due to fear of a ghost that was reputed to stay there. Vachaspati Mahasaya described the forms of ghosts to him in some detail, and the boy became more frightened. However, he also had a strong desire to eat the star-apples.

He then spoke to the mother of a friend who was reputed to be expert in the occult, and she told him that there is no fear of ghosts as long as one chants the name of Rama. By way of an experiment, the boy went to the orchard constantly calling out the name of Rama. He then became convinced in his heart that chanting the name of Rama was protection against ghosts. From that time on he was not afraid to go out at dusk, and when he did he constantly chanted the holy name of Rama.

Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura recalls:

At dusk I would always utter the name of Rama. When walking about in the streets and alleys I always chanted the name of Rama. I obtained such great satisfaction in my mind [from this] that for many days afterwards I took this medicine against ghosts. I heard that a ghost lived in the homa [sacrificial fire] building. Uttering the name of Rama, I chased the ghost away …

Upon his reaching the age of twelve, in 1850-51, his mother arranged a marriage with a girl from Ranaghat named Sayamani. She hoped to improve the family fortunes by this arrangement. Childhood marriages were not uncommon at that time in Bengal. Such marriages were generally arranged by astrological calculation so that the partners would be compatible, and the couple usually came from similar family backgrounds. The couple generally did not live together until they reached maturity. Bhaktivinoda Thakur went to live for a while in his father-in-law’s house, and his nanny came to care for him.

Not long after this his maternal grandfather died. After the sraddha ceremony (funeral rites) the Thakur returned to Ula and tried to manage the shambles that had become of his grandfather’s estate. He was not well-equipped to do it, being young and inexperienced, but by various means, family debts were paid off. However, it seemed that there was never enough money, and his family experienced suffering on this account, as they were accustomed to a comfortable existence. The Thakur recounts:

Everybody thought that my mother had a lot of money and jewelry. Except for a few properties (which probably brought in a small rental payment) all her wealth was lost. … There were numerous expenses and no money remained in my mother’s hand. I was in complete anxiety. My grandfather’s house was huge. The guards were few, and I was afraid of thieves at nights. I thus gave the guards bamboo rods to carry. In this regard I was not lax.

The Thakura met a mystic guru, a former cobbler, whose name was Goloka. His philosophy had some outward similarities to Vaisnavism, but their eclectic beliefs concluded that the impersonal Brahman was the highest manifestation of transcendence. Goloka had many supernatural powers, and Kedaranatha was impressed by him. The guru cured Kedaranatha of a number of ailments by giving him certain mantras, and medicinal substances to be taken were shown to him in dreams. One day Goloka predicted that Kedaranatha’s boyhood home, Ula, would soon be almost entirely destroyed. The people there would die from fever and disease. He also predicted that Kedaranatha would become a great Vaisnava. Both predictions would prove to be true.

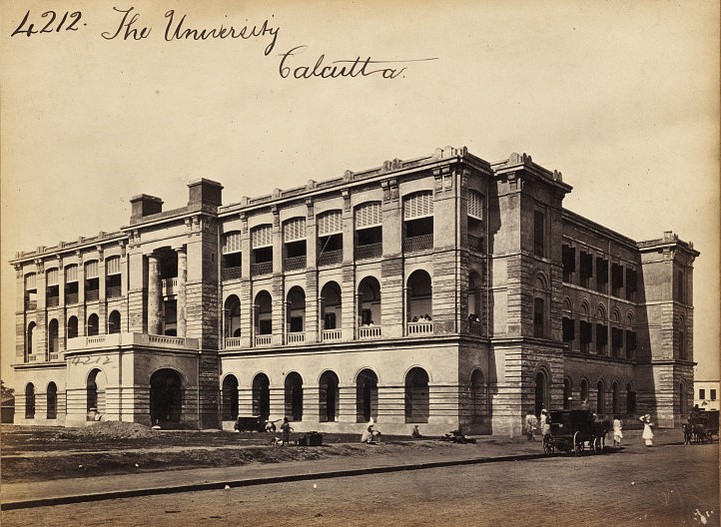

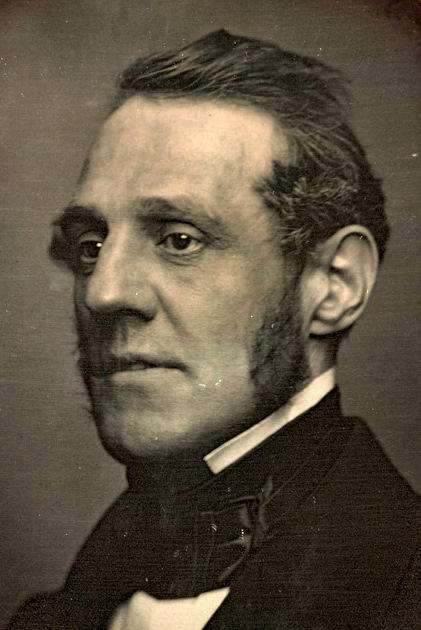

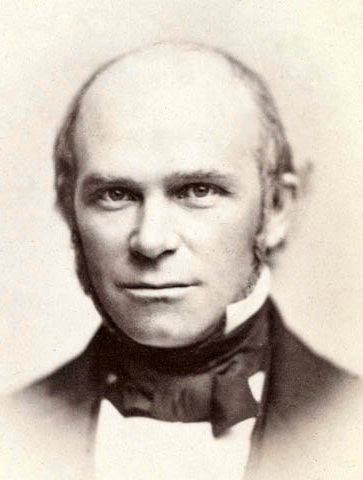

In 1856 Bhaktivinoda Thakur enrolled in the Hindu School in Calcutta, which later became known as the University of Calcutta. He became the student of a reputed scholar and author, and was recognized and praised for his poetry, some of which was published in the Literary Gazette. Some of his classmates called him “Mr. ABC.” An Englishman George Thompson, who was a former member of British parliament, taught him the art of oratory.

[George Thompson (1804–1878) was best known as a public agitator against slavery in the British Colonies, for which cause he lectured in large towns in Great Britain and visited America in 1834 and 1851, and during the civil war of 1860–4. He visited India in 1842 and worked with the Bengal Landholders’ Society, regarding what he called the Hill Cooly system of slavery, the oppressive land-tax and the opium and salt monopolies. He was a prominent member of the British India Society of London, which was formed in 1840 and lectured on Indian topics in England, with a view to advance the claims of the Indian people to better government. He formed a Branch of this Society in Calcutta in 1843. In India, he was appointed Ambassador of the Emperor of Delhi. Thompson again visited India in 1855, but left it in the mutiny of 1857-8. He was the M.P. for the Tower Hamlets in 1847–52. Thompson was renowned as an eloquent speaker and is said to have been brilliant in conversation.]

[Dictionary of Indian Biography]

The young Thakur spent much time studying in various libraries, and was tutored by the Christian missionaries. He also studied the Koran. He was always very liberal and non-sectarian in his attitude towards life, politics and religion. He spoke at the British Indian Society, and was invited to become a member.

Around 1857 he went to Ula to visit his family. He was eighteen at this time. The scene was one of great despair. There had been an outbreak of cholera and many persons had died, generally within four or five hours of symptoms first appearing. The words of the mystic guru had come true. When he arrived at the family home, he learned that his sister had died. His mother and paternal grandmother were there in great distress, and his mother, though recovering, had been delirious for many days. Ula was the scene of a great disaster. Hundreds had died.

Staying at the house of his uncle, Kali Krishna, in Calcutta, Bhaktivinoda Thakur cared for his mother and grandmother. Times were difficult. He had no money and there were great hardships. He tried to take the college examination but was unable to prepare properly in an atmosphere of anxiety about his family members. At this time he read many books on the science of God and religion, including Sanskrit books, as well as Western philosophers like Kant, Goethe, Hegel, Swedenborg, Hume, Schopenhauer, Voltaire etc. Following a recitation and ensuing debate at the British Indian Society, he became well known as a philosopher and logician. The Thakur was fascinated by theism, and spent much time studying the Bible and Koran. He developed deep faith in Jesus Christ.

In 1857, Thakur Bhaktivinoda was struggling to complete his education and was unable to properly support and provide a home for his wife and mother. At this time his wife, now twelve years old, begged him to be allowed to come and stay with him in Calcutta, and he assured her that she would be allowed to come when he found employment. In desperation, he applied for the post of accountant with a sugar merchant, who attempted to give him some training.

The young man was surprised to see the cheating involved:

When I purchased a large quantity of sugar I obtained an [extra] sack of sugar. I noticed this and considered it irreligious to cheat. I therefore informed the merchant …

The merchant advised him that it would be better for him to get a job as a teacher – that business life would be too difficult for one of his principles. He got a job as a second grade teacher in the Hindu Charitable Institution School, which he had earlier attended. He was about nineteen at this time.

In 1858, Bhaktivinode Thakur’s paternal grandfather, Rajavallabha Datta, contacted him from where he was living at Chotimangalpur in Orissa. His grandfather’s family had been very wealthy, and at one time had owned the land in Calcutta where Fort William, a large British garrison covering many acres, was built. He had been a wealthy and influential man in Calcutta, but had lost much of his land and wealth, and was now living a renounced life in the countryside in Orissa. He wrote:

I will not live much longer. I desire to see you immediately. If you come quickly, then I will be able to see you, otherwise it will not be possible.

Accompanied by his wife and mother, the Thakur set out for Orissa. There were great obstacles on the journey. When they finally arrived, his grandfather openly wept out of affection when he saw them. Srila Thakur Bhaktivinoda observed the activities and schedule of his grandfather. He kept many cows and there was plenty of yoghurt and ghee always. He also had many other animals, including peacocks and swans. Srila Bhaktivinoda’s grandfather, though elderly, ate nothing at all during the day. At midnight he would eat kachauries (stuffed pastries) full of chillies, or milk cooked with date sugar. He wore the saffron cloth of a sannyasi. During the day he constantly chanted japa.

The Thakur saw him pull cobras out of their holes and kill them with his shoes. He was very strong and did not appear to be ill. According to one of the early biographers of Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur, Pandit Chattopadhaya:

That gentleman had once been a conspicuous figure in the ‘City of Palaces’ (Calcutta) and retired to a lonely place in Orissa to spend the rest of his life as an ascetic. He could predict the future and knew when he would die. He could commune with supernatural beings.

Rajavallabha Datta worshiped Lord Jagannath and Radha-Madhava in his house. He made a horoscope for his grandson and predicted that he would secure a good position at the age of twenty-seven. Though he appeared well, his grandfather told the Thakur:

Do not leave here for one or two days. My life is coming to an end.

Three days later, his grandfather had a slight fever. He sat upon a bed in the courtyard of his house, leaning against a bolster, and he began to continuously chant the holy name. Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur recounts:

He called for me and said, ‘After my death, do not tarry too many days in this place. Whatever work you do by the age of twenty-seven will be your principle occupation. You will become a great Vaisnava. I give you all my blessings.’ Immediately after saying this, his life left him, bursting out from the top of his head. Such an amazing death is rarely seen.

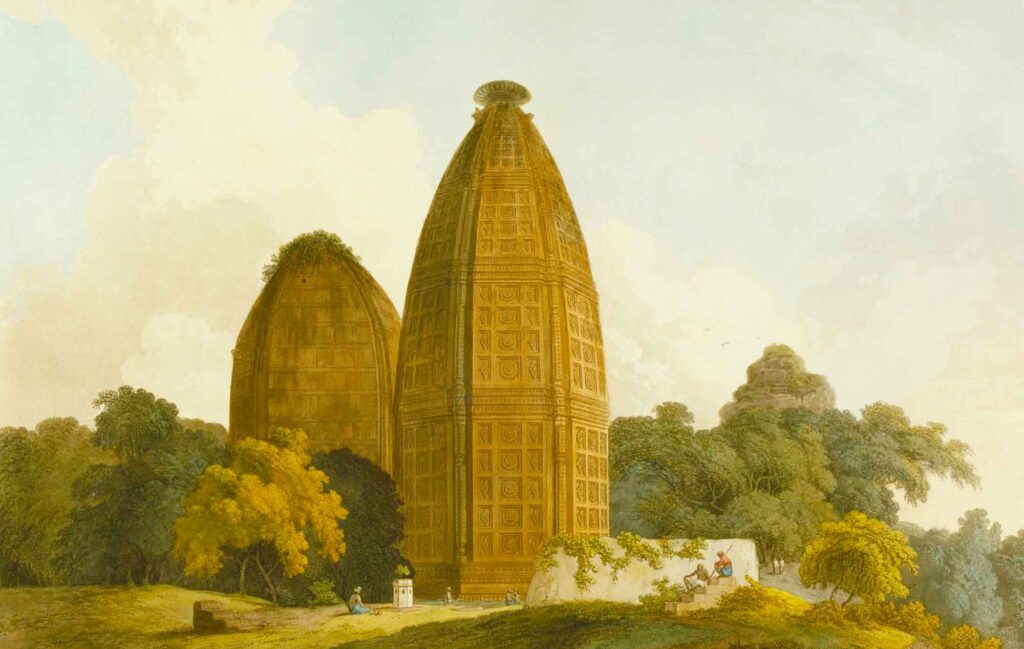

In 1859 Bhaktivinoda Thakur took the Teacher’s Examination and received his ticket of qualification. He was twenty-one years old. After attending the Candana Festival in Jagannath Puri and touring various temples in Orissa, he receved a teacher’s position in Cuttack in Orissa, with a salary of twenty rupees per month. Expenses were minimal in Orissa, and they began to live more comfortably. He read all of the books on philosophy in the Cuttack school library.

Bhaktivinoda Thakur was befriended by Mr. Healey, the Assistant Magistrate and School Secretary at Cuttack, who heard him in debate and was much impressed by his power of oratory. Mr. Healey took a special interest in the Thakur, whom he obviously perceived to be a very gifted and morally upright personality, and helped him further his education. By 1860, the Thakur was given the position of Headmaster of the Bhadra School, with a salary of forty-five rupees per month. He wrote and had published a book called Maths of Orissa at this time.

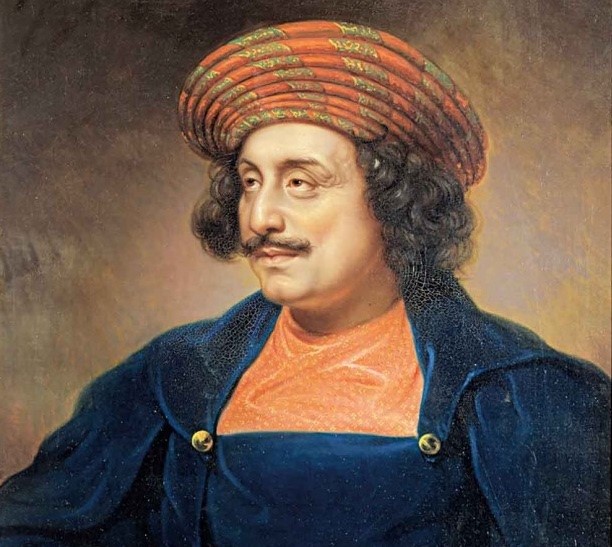

While touring the temples of Orissa, which had been done at the request of his grandfather, the Thakur kept a careful record of all that he observed. This record was published as a pamphlet in 1860, and was later quoted and praised in a book titled Orissa, written by Sir William Hunter, a reputed British historian, which was published in 1872. At the end of 1860 he received another promotion, and received a teacher’s appointment at Midnapur in Orissa. The Thakur found the climate conducive for health at Midnapur, but the spiritual atmosphere was disturbed due to conflict between the followers of Rammohun Ray and the conservative, caste-conscious Hindus.

Rammohun Ray, the inventor of the “Brahmo” philosophy, was a reformer who rejected the caste system and many Vedic religious practices and beliefs, including those of Lord Chaitanya and other schools of Vaisnavism. He described much of Vedic teaching, especially the Puranas and historical accounts like the Mahabharata, Ramayana and Srimad Bhagavatam as being mythological. He was influenced by the impersonalist philosophy of Shankara, and favoured the logic and ideas of Western philosophers such as Aristotle, Locke, Hume and many others over much of traditional Indian thought.

Vaisnava traditions and ideas were generally out of favour with the “intellectual” new generation of Bengali youth, who disliked and rejected the older generation of conservative Hindus, who would censure them for aping Western liberality and [bad] habits. Despite his intense study of and interest in Western philosophies and ideas, Bhaktivinoda Thakur didn’t accept Rammohun’s impersonalist theories. He would sometimes travel to Calcutta for discussions with his old friends and notes:

… the religion of the Brahmos [philosophy of Rammohun] was not good. I thought that the brotherly love philosophy taught by Jesus Christ was best … the taste [derived from such worship] was due to devotion. I read all the books written by *Theodore Parker and others, and books on Unitarianism I got from Calcutta. Because of [such books], my mind was attracted toward the devotion of Jesus. From the time of my childhood I had faith in bhakti. During the time I was in Ula, hearing Hari-kirtan produced bliss in me.

[*Theodore Parker (1810-1860), was an American Unitarian clergyman and social reformer, who promoted the anti-slavery cause. Unitarianism is a non-trinitarian Christian theological movement that believes that the God in Christianity is one singular entity, as opposed to a Trinity.]

Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur also recalled how a servant of his grandfather had chastised some so-called Vaisnavas for catching fish, telling them that it is very bad for Vaisnavas to kill other living entities. When the boy heard these exchanges he immediately could understand the truth of the statements. He had observed the practices of the Shaktas (followers of Goddess Durga) who sacrificed animals and ate the meat from his youth, and considered these activities very “ignoble” (dishonorable and degraded). The Thakur further recalled seeing in his youth a Vaisnava called Jaga who danced and chanted, crying torrents of tears, in the ecstasy of singing the Holy Name, and he remembered how the Karta-bhaja fakir (a disciple of Goloka) had cured him.

There was some substance in the Vaisnava religion. There was bhakti-rasa, and therefore I had some faith therein … When I went to Calcutta I would meet with Baro Dada [“Big Brother” – Dvijendranath Tagore] and hear a little of the Brahmo dharma … but there was a natural aversion towards the Brahmo [impersonalist] religion in my mind. I would deliberate and converse a good deal with Dal Saheb [a Christian former teacher], along with other missionaries, and the Christian religion, in comparison to the Brahmo religion, was far superior.

Toward the end of 1861, Sayamani, Bhaktivinoda Thakur’s first wife died, leaving him with a ten-month-old son. He was twenty-three years old at this time and was sick with a swelling in his lungs. His mother tried to raise the child but was old and found it difficult. The Thakur states that he prayed to God for help at this time. He later stated that at this time he had conviction both in the formless conception of God as well as the spiritual form of God, but could not determine how both concepts were simultaneously true.

He remarried two months later to a girl named Lalita, daughter of Gangamaya Raya of Jakpur, who later became known as Srimati Bhagavati Devi. Following in the footsteps of her husband, she was a sincere Vaisnavi of noble character, peaceful and accomplished in all she did. The Thakur was criticized by some of his relatives for marrying again so quickly, but personally concluded there was no blame attached to it. Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur was then offered the position of tax-collector and clerk in the Collectorate, a position which was not especially palatable to the Thakur.

While living in Chuadanga, Thakur Bhaktivinoda took the law examination in Burdwan, with the encouragement of Mr. Heiley. Heiley wanted to secure for him a position which was superior to a mere clerical post. He appealed to Sir Ashley Eden on his behalf, and in February of 1866 the Thakur was appointed Special Deputy Registrar of Assurances with powers of a Deputy Magistrate. The position was at Chapra in the Nadia District of West Bengal. He was twenty-seven at this time – his grandfather’s prediction had proved to be true.

In 1866 Thakur Bhaktivinoda spent thirteen days in Western India, where he toured Vrindavan, Mathura, Agra, Prayag, Mrijpur and Kasi. In his biography he humbly states that at this time his bhakti was still mixed with jnana, and therefore he did not experience the pure happiness of bhakti-rasa in Vrindavan. He was happy to see the temples, but due to his increasing humility, he felt in retrospect that he had not properly honoured the devotees there.

In 1867 the Thakur passed a government service examination, and when a separate Judicial Department was set up by the Bengali civil service in 1868, the Thakur was appointed Deputy Magistrate of Dinajpur.

To his delight he found many Vaisnavas residing there under the patronage of the great Zamindar (landowner) of Dinajpur, Ray Saheb Kamala Lochan, who was descended from a great devotee of Lord Chaitanya. The Thakur wrote:

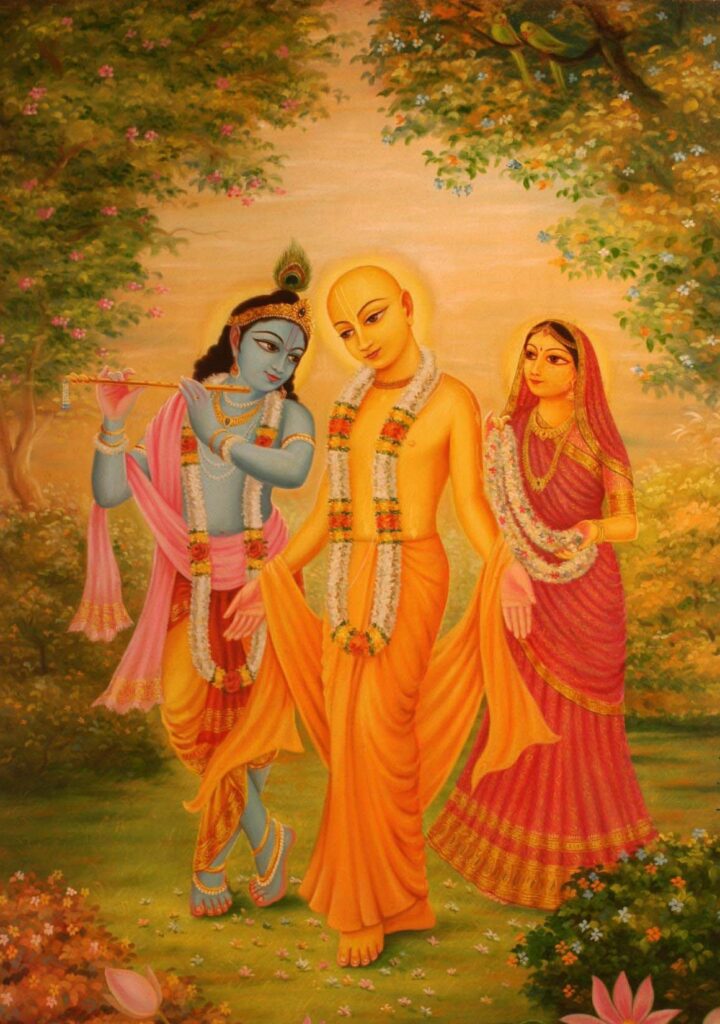

In Dinajpur the Vaisnava religion was fairly strong due to Ray Kamala Lochan Saheb. There were many renunciates (babajis) and goswamis coming and going there. A few wealthy persons were supporting many assemblies of brahmana pandits. Respectable gentlemen would regularly come and discuss the Vaisnava dharma with me. I had a desire to know what the genuine Vaisnava dharma was. I wrote to our agent Pratap Chandra Ray, and he sent a published translation of Srimad Bhagavatam and Sri Chaitanya-caritamrta. I also bought a book called Bhakta-mala.

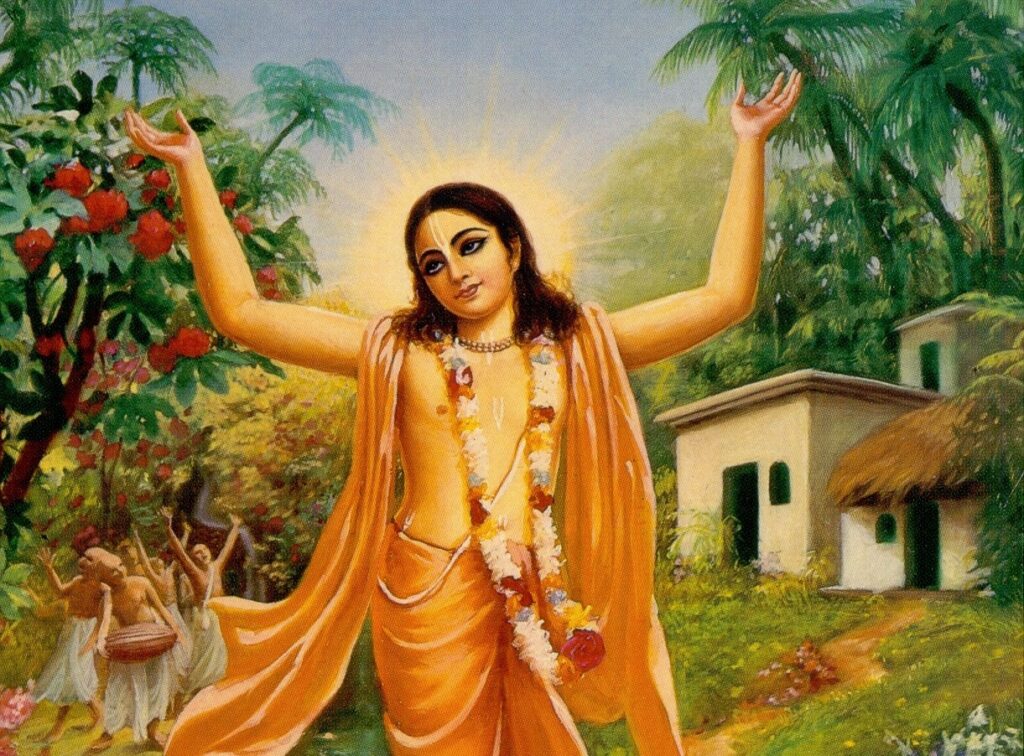

On my first reading of Chaitanya-caritamrta I developed some faith in Sri Chaitanya. On the second reading I understood that there was no pandit equal to Sri Chaitanya. Then I had a doubt: being such a learned scholar and having manifested the reality of love of Godhead to such an extent, how is it that He recommends the worship of the improper character of Krishna? I was initially amazed at this, and I thought about it deeply. Afterwards, I prayed to the Lord with great humility, ‘O Lord! Please let me understand the mystery of this matter.’

The mercy of God is without limit. Seeing my eagerness and humbleness, within a few days He bestowed His mercy upon me and supplied the intelligence by which I could understand. I then understood that the truth of Krishna is very deep and confidential and the highest principle of the science of Godhead. From this point on, I knew God as Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu.

I made an effort to always speak with renounced Vaisnava pandits, and I came to understand many aspects of the Vaisnava dharma. In my very childhood the seed of faith in the Vaisnava dharma was planted in my heart, and now it had sprouted. From the very beginning I experienced anuraga (spontaneous devotion) and it was very wonderful. Day and night I liked to read about Krishna-tattva.

[Excerpts from “The Seventh Goswami” by Rupa Vilas Das and Bhaktivinoda Thakur’s Autobiography]

Comment

Bloody brilliant!