After five years of service at Jagannatha Puri, the Thakur had to leave to settle urgent family business. He was then posted to various other towns in Bengal. He spent time at Arraria before, in November 1877, transferring to Mahibarekha, near Calcutta, where he dealt with serious problems of police corruption. Next he was transferred to Bhadrak, where he was promoted to Deputy Magistrate. At this time Mr. Robbins wrote him a very affectionate letter, practically begging him to return to Puri. Indeed, following his move from Puri, there was a tug-of-war between various government officials to secure the Thakur’s services.

Narail

In July 1878, the Government issued the Thakur Summary Power, and in August he was transferred to Narail in Bengal, a town near the city of Khulna, both of which are today situated in south-west Bangladesh. In Narail there was a good deal of service for the Thakur, and he became very popular with the townsfolk. He took every opportunity to tour the region, and was met with great affection by all of the people, who would serenade him with the Holy Name when he arrived in their villages.

Narail

In 1880, while residing in Narail, the Thakur published Krishna-samhita, a book which was popular amongst devotees, and which received high critical acclaim amongst Indian and European scholars alike. Dr. Reinhold Rost, a famous oriental scholar and linguist of the day, wrote an appreciative letter to the Thakur:

… thank you … for the kind present of your ‘Sree Krishna Samhita.’ By representing Krishna’s character and his worship in a more sublime and transcendent light than has hitherto been the custom to regard him in, you have rendered an essential service to your co-religionists …

In 1880 the Thakur also published a book of Vaishnava songs, called Kalyana-kalpataru – “The Desire Tree of Auspiciousness.” This book was very well-received and extremely popular, and one of the Thakur’s biographers correctly states:

… it may very truly be termed an immortal work and stands on the same level as the divine writings of Narottama das Thakur.

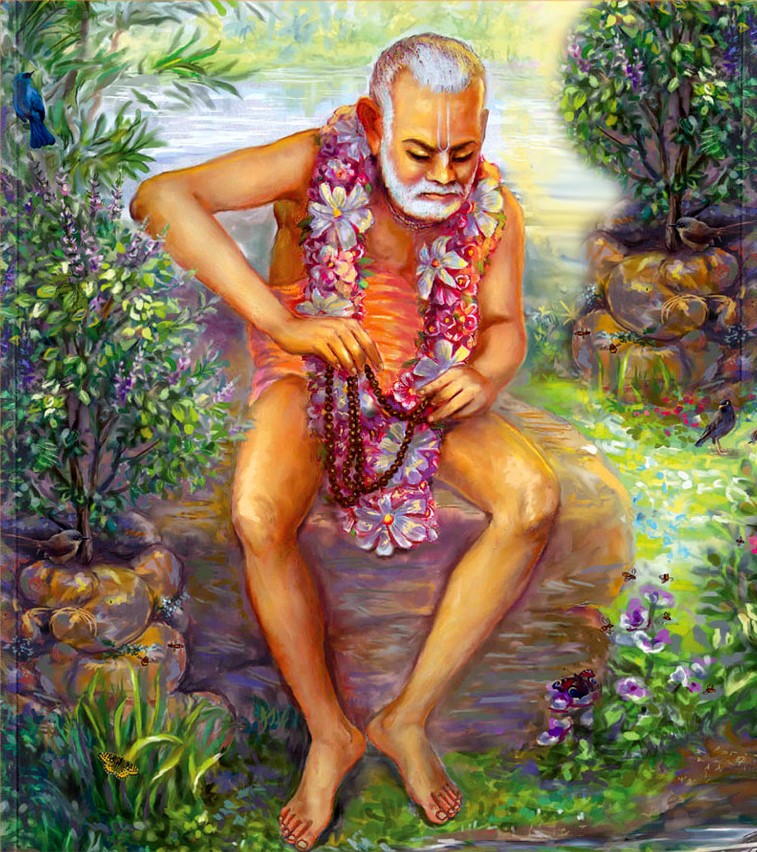

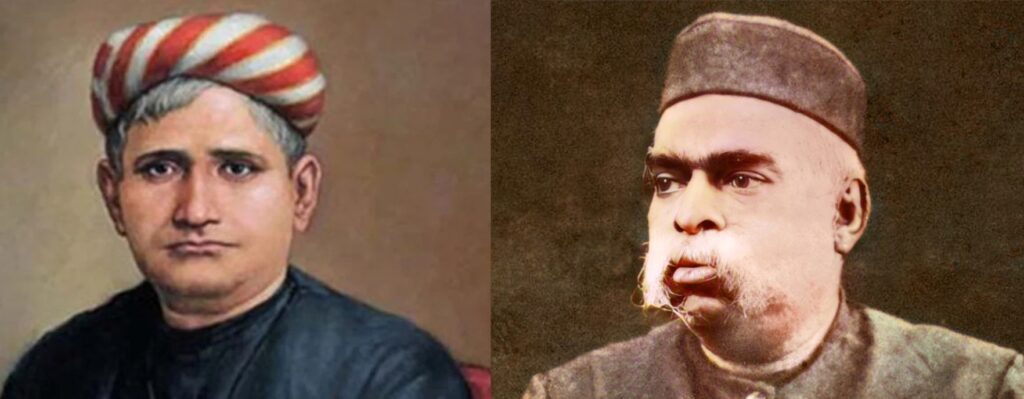

Narottam Das Thakur and Bhaktivinoda Thakur

The Thakur reports in his autobiography that the songbook was “received with affection.”

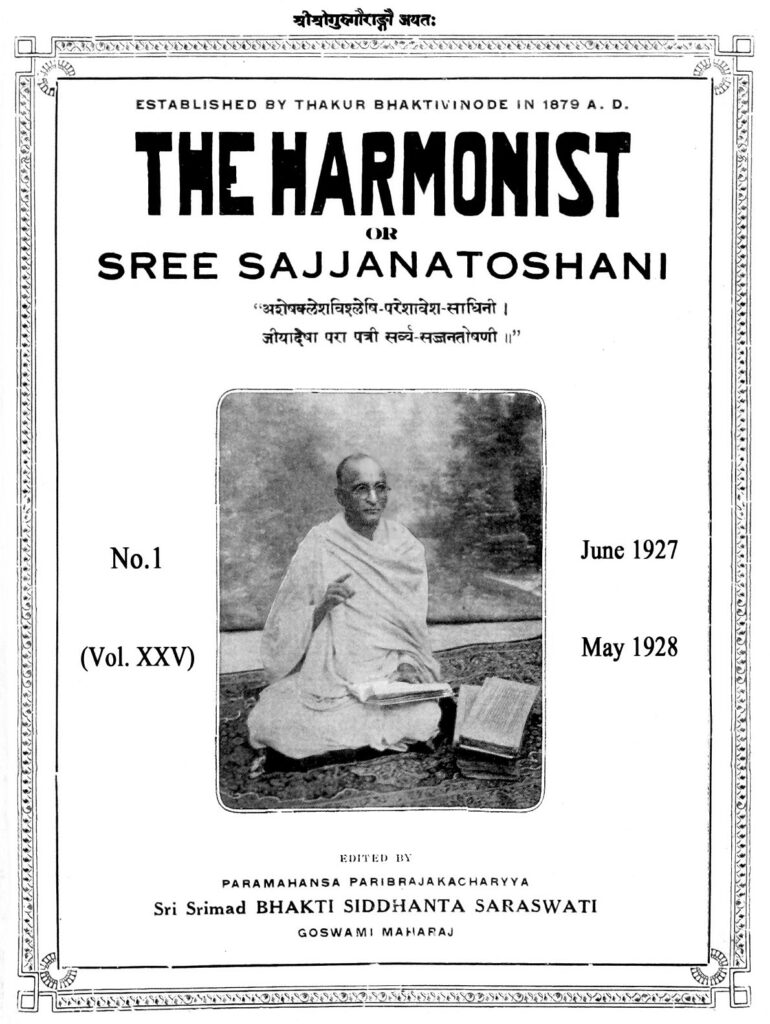

While in Narail the Thakur started a monthly Vaisnava journal, Sajjana-tosani, which was written in Bengali. This magazine was intended to educate the learned and influential men of Bengal about the wonderful nature of Lord Chaitanya’s mission and teachings, the truth of which had been largely obscured with the passing of time. Seventeen volumes were published over the years. Included were many articles by Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur, and after his departure, his son, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakur took up the work, publishing it in many languages, including an English edition called “The Harmonist.”

Initiation

The Thakur was feeling an urgent need to take initiation from a suitable guru. He relates:

I had been searching for a suitable guru for a long time, but I did not obtain one. I was very unhappy … I was feeling very anxious, and in a dream Mahaprabhu diminished my unhappiness. In that dream I received a little hint. That very day I became happy. One or two days later Gurudeva wrote a letter to me saying, ‘I will soon come and give you diksha (initiation).’

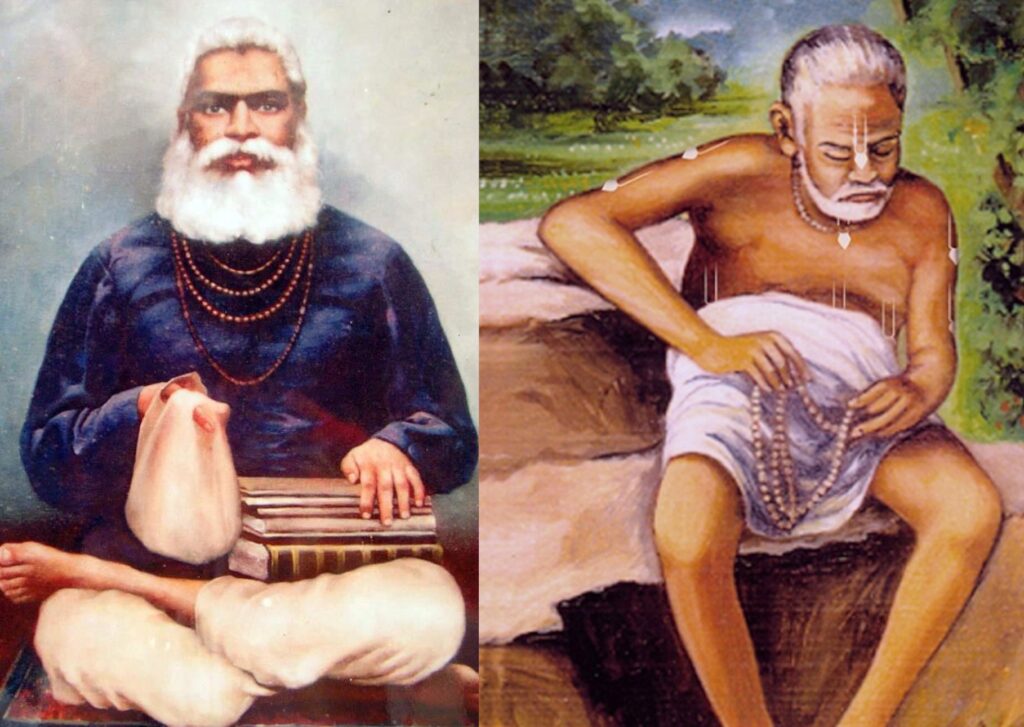

A poor quality picture of Vipin-vihari Goswami

After this, Vipin-vihari Goswami (1850-1919) visited the Thakur at Narail and gave him Vaishnava (diksha) initiation. Vipin-vihari Goswami was descended from the Jahnava family of Baghnapara. He was coming in the disciplic succession from Sri Gadadhar Pandit, the plenary portion of Srimati Radharani. The followers of this line generally worship Sri Gaura-Gadadhar.

Bhaktivinoda Thakur’s Gaura-Gadadhara Deities

Towards the close of the Thakur’s stay in Narail, in 1881, the Thakur decided to once again visit Vrindavan. It was fifteen years (1866) since he had last visited the Holy Dhama, and he set out on a three-month pilgrimage with his wife, a young Lalita Prasad, and two servants.

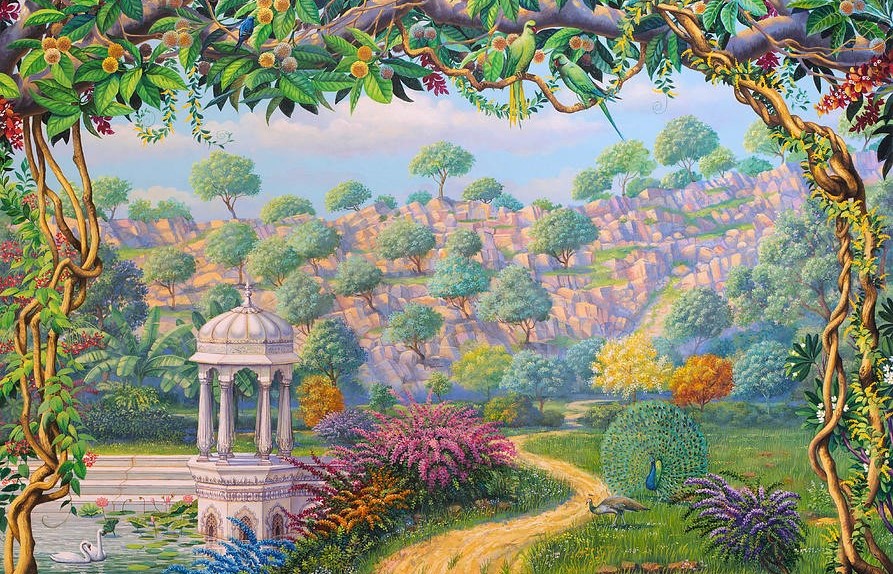

Govardhan Hill

After arriving, the Thakur began to suffer from fever. He prayed to the Lord to relieve him of the fever for the duration of his stay in the Dhama, saying that afterwards, if He liked the Lord could again purify him with fever. The fever vanished.

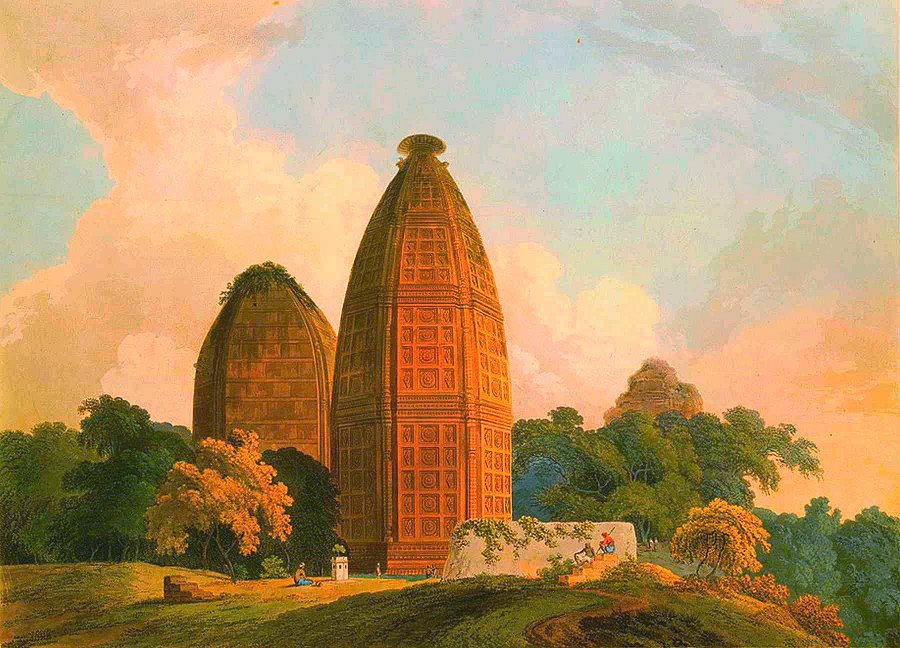

Madan-Mohan Temple in Vrindavan

While he was in Vrindavan, Thakur Bhaktivinoda associated with different sadhus. He took prasadam at the kunja (garden) of Rupa das Babaji and heard for the first time the Dasasloki of Nimbarkacarya, the great acharya of the “Kumara Sampradaya,” the disciplic succession coming from Sanat Kumara, one of the four Kumaras, the young brahmacary sons of Lord Brahma.

The Four Kumaras and Nimbarkacarya

Meeting Srila Jagannath Das Babaji

It was at this time Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur first met Srila Jagannath Das Babaji. The great Babaji gave many spiritual instructions to Srila Thakur Bhaktivinoda, and he became the instructing spiritual master (siksha guru) of the Thakur. Together these two great Vaisnavas discovered the birth place of Lord Chaitanya Mahaprabhu.

Jagannath das Babaji divided his time in later years between Sri Vrindavan-dhama and Sri-Mayapur-dhama, staying six months in one and then six months in the other. He was the spiritual master of the Gaudiya Vaisnava community in Navadvipa and a perfectly realized soul. He became increasingly important to the Thakur as a source of spiritual inspiration and direction, and in the listing of the Brahma-Madhva-Gaudiya sampradaya, our line of disciplic succession as given by Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakur, the siksha link between Thakur Bhaktivinoda and Jagannath das Babaji has been given paramount importance.

In his song “Sri-Guru-Parampara” Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati has stated:

… Jagannath das Babaji was a very prominent acharya after Baladeva Vidyabhusana and was the beloved siksha guru of Srila Sac-cid-ananda Bhaktivinoda. Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur’s intimate friend and associate was the eminent maha-bhagavata Sri Gaurakisora das Babaji, whose sole joy was found in hari-bhajana …

Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur called Jagannath Das Babaji “Commander-in-Chief of the Vaishnavas.”

Punishing the Kanjhars

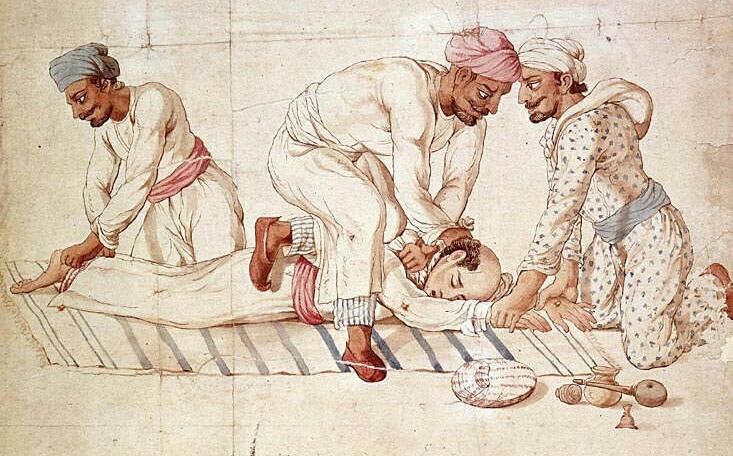

Kanjhar dacoits strangling a traveller

While traveling in Vrindavan Dhama to places like Radha-kunda, Govardhan Hill, etc., the Thakur came to know of a band of dacoits (bandits) called the Kanjhars. Satkan Chattopadhyaya Siddhanta Bhushan, in “A Glimpse into the Life of Thakur Bhaktivinode”, said of the Kanjhars:

These powerful bandits spread all over the roads surrounding that holy place and used to work havoc on innocent pilgrims for the purpose of extorting the last farthing they possessed. We cannot possibly recount how many murders were committed by these brutes to gain their selfish ends as these accounts hardly come to light in facts and figures. It was said that these ruffians had at their back some unscrupulous persons who had the authority and power over the people. It was through his (Bhaktivinoda Thakur’s) undaunted will and untiring labour for several months that the whole fact was brought to the notice of the Government, and a special Commissioner appointed to crush the whole machinery set up by these Kanjhars against these innocent pilgrims. The result was marvelous and the name of the Kanjhars has forever been extirpated from the earth.

Dacoits in prison

In his autobiography the Thakur humbly gives this event a very brief mention:

Going by palanquin I took darshan of Radha-kunda and Govardhana. There I experienced the spitefulness of the Kanjhars, so I made arrangements to put an end to it.

Bhakti Bhavan, Barasat and Bankim Chandra

Following his pilgrimage to Vrindavan, the Thakur was transferred to Jessore. He said of his stay in Jessore:

The place was exceedingly abominable. Fever took its residence in Jessore (in accordance with my prayer in Vrindavan).

The Thakur was determined to establish a place in Calcutta for his preaching work. He found a suitable place at 181 Manikatal Street (presently Ramesh Dutt Street), which he later called “Bhakti Bhavan.”

Bhakti Bhavan in recent times

This was to be the site of many learned discourses, meetings with eminent personalities and the writing of many articles and books. The worship of a Giridhari-sila, (Deity stone from Govardhan Hill) which had been given to him by Jagannath das Babaji Maharaja, was also to be established. The house cost 6,000 rupees, and needed repairs which the Thakur had carried out. His family, though initially dubious and reluctant to move into the house, upon seeing it newly renovated were happy to move in.

Deities at Bhakti Bhavan showing Govardhan Silas on bottom shelf

The Thakur then got a post at nearby Barasat with the help of Commissioner Peacock, who had become very favourably disposed to him, and in 1881 he stayed at Barasat with two of his sons, Radhika and Kamal. His wife stayed at Calcutta with the rest of the family, but came to Barasat when the Thakur became ill and needed care. Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur was frequently troubled by fevers and various other ailments throughout his life, but his determination to serve Krishna never diminished even slightly – he always accomplished the superhuman work of a spiritual genius, while performing his material duties faultlessly.

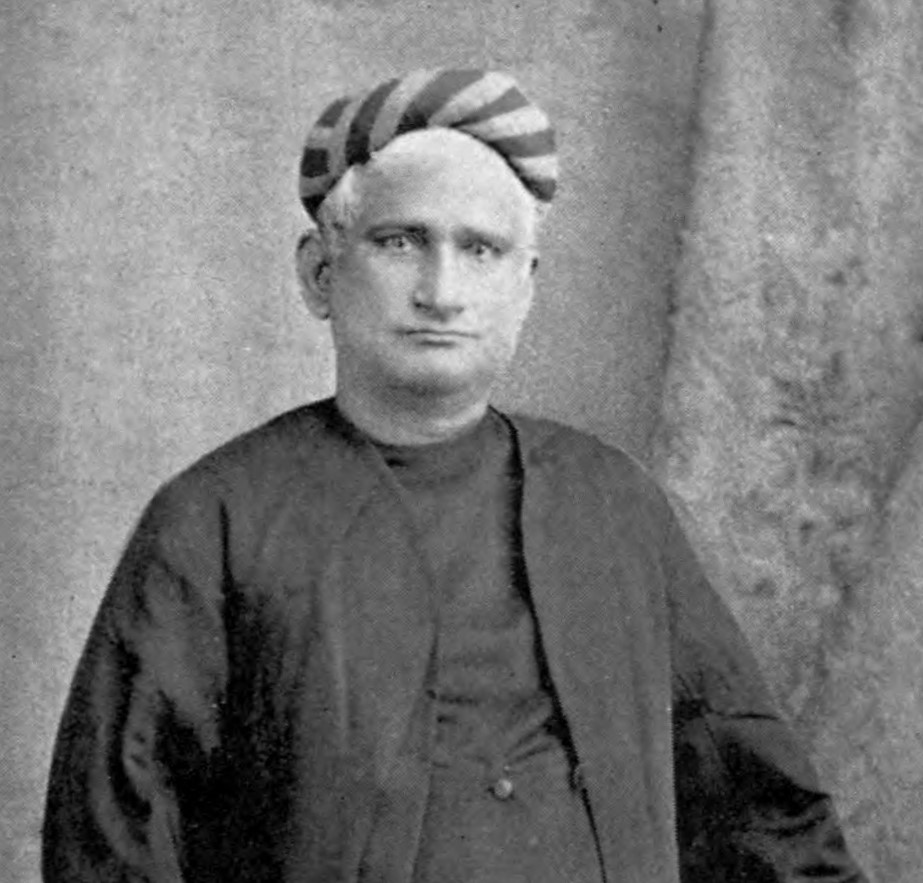

Bankim Chandra

During his stay at Barasat, the Thakur met the famous Bengali novelist, Bankim Chandra, who had just finished a book on Krishna called Krishnacarita. The author had been greatly influenced by English and French philosophers, although he had much regard for traditional Vaisnavism. Bankim Chandra heard that the Thakur was an authority on Krishna, as well as an expert writer, so he wanted to take the opportunity to show him the book. Unfortunately, the book was full of all kinds of Westernised concepts and various mundane speculations. It presented Krishna as an ordinary person who had many good qualities.

Taking little food or sleep for four days, the Thakur put forward many verses and arguments from the scriptures, proving Krishna’s position as the Supreme Personality of Godhead. The author, being much swayed by the conviction and authority of the Thakur’s presentation, corrected many of the errors in his book, bringing them more into line with the transcendental teachings of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. The author was subsequently criticized by scholars for presenting Puranic histories of Krishna’s activities as literal facts rather than “pure legends, myths, fables and traditions.” Such criticism may be seen as a kind of certificate of success for the Thakur, whose aim had been to convince Bankim Chandra of just this: that Krishna was the Absolute Truth and His Transcendental pastimes were literal facts.

The Thakur had duties both in Barasat and nearby Naihati, and he experienced much trouble from the many ill-natured townsfolk who, in order to draw attention to themselves, tried to create mischief for him in various ways. He stayed there for two years, but he always felt eager to leave, due to the quarrelsome inhabitants, as well as the constant threat of malaria that was prevalent in the area.

A Flood of Books

Towards the end of his stay in Barasat, the Thakur received some important books from an advocate friend, Babu Sarada Charan Mitra, who later became a Calcutta High Court Justice. Sarada Charan Mitra wrote the introduction to a biography of Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur called “A Glimpse into the Life of Thakur Bhaktivinode,” which was published in 1916. Among the books sent were the commentaries on Bhagavad-gita and Srimad Bhagavatam by Srila Visvanatha Cakravarti Thakur.

Visvanatha Cakravarti Thakur

At the request of his friend, Thakur Bhaktivinoda took up the task of publishing a good edition of the Bhagavad-gita with the commentary by Visvanatha Cakravarti Thakurand his own commentary, called Rasika-ranjana. This was published in 1886. The popular novelist Bankim Chandra wrote the introduction, expressing his indebtedness to Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur and impressing upon the Bengali public their good fortune in receiving such a great work. All copies of the book quickly sold out.

In 1883 the Thakur came across a Sanskrit manuscript called Nitya-rupa-samsthapanam, the English translation of which is Establishing God’s Eternal Form. The manuscript, written by Pandit Mohan Gosvami Nyaya-ratna, a descendant of Lord Nityananda, was a very scholarly presentation on this important point of Vaishnava theology, and the Thakur wrote a review of the book in English for a European journal, so that Westerners might be attracted to the subject matter. He comments:

The object of this book is to prove the eternal spiritual form of the Deity. The subject is certainly not a new one, but in the latter part of the nineteenth century, when science is so deeply engaged in its warfare with popular belief, it looks like a new subject inviting the attention of the public. Amongst the scientific beliefs that have come to India along with the British rule, the metaphysical inference that the Deity has no form has been accepted as one of the most philosophical acquisitions that man has ever obtained. The current of the abstruse [difficult to understand] idea of a formless Brahma [Brahman – impersonal absolute] which has invaded thought and worship in India since the time of Pandit Sankaracarya has, with the existence of the European idea of a formless God, become so much extended, especially in the minds of the youngsters of this country, that if an attempt is made to establish the fact that God has an external form, it is hooted down as an act of stupidity.

Formless Brahman and Personal Form of God

“External” is not used in the above sentence to mean “material,” but is used to mean an eternal spiritual form which can be visualized as distinct from His internal essence. The Thakur cites numerous scholarly sources of the Pandit, including the Sandarbhas of Srila Jiva Goswami, the Vedanta Sutra and the commentaries by the Vaisnava acaryas. The Thakur expresses his intent to “reproduce in the modern style the arguments of Prabhu Upendra Mohan Goswami.” Some excerpts are reproduced below:

There is one more argument of the rationalist which we shall take time to consider. He naturally questions the possibility of the manifestation in nature of that Supernatural form. We have read in the Hindu scriptures and in the lives of holy men such as Prahlad and Dhruva that God made His appearance in nature in His form of spirit and acted with men as one of their friends.

We are not prepared, in consideration of our short time and space, to prove that the statements made in the sastras were all historically true, but we must show that the principle taught in these statements is philosophically safe. God is spiritually Almighty and has the power to overcome all conditions of matter, space and time. It is certainly His power and privilege to be aloof from matter in the position of His Sri Vigraha [Deity form], and at the same time to exist in the universe as its soul [Lord Paramatma].

Transcendental Deity Form and Lord Paramatma

In the exercise of His liberty and sovereignty over matter and space, it is not hard to believe that He may now and then, or at all times, be pleased to make a manifestation in nature, sometimes accepting her rules and sometimes rejecting them at His pleasure. The conclusion is that the universe in general and man in particular can never by a rule enjoy a sight of the All Beautiful in the scene of matter, but God of His own freedom can exhibit Himself in supercession of all rules and prove His dominion over all He created.

Man sees Him when he regains his pure spiritual nature, but God shows Himself out of His kindness to man whenever He is pleased to do so. Holy men to whom God has been pleased to show His spiritual form have often attempted to picture it to their fellow brethren. The picture, whether it be by pencil, chisel or pen, is always made through the medium of matter, and hence a degree of grossness [appearance of consisting of material elements] has all along attended the representations.

This emblematic [symbolic] exhibition of spiritual impressions is far from being open to the charge of idolatry. Those who rationally conceive the idea of God, and by the assistance of the imagination create an image, are certainly open to the charge. There is one absolute truth at the bottom of this important question. It is this: Nature has indeed a relation to spirit. What is that relation? As far as we have been instructed by the inner Tutor, we may safely say that spirit is the perfect model and nature is the copy which is full of imperfections.

An imagined image of God is an idol. The spiritual form revealed by the Lord to pure souls is a Deity

Draw inferences from the side of nature and press them upon the Deity, they will ever remain gross and imperfect. Draw from the spirit inside and push your impressions at first to the mind and then to the body, you simply spiritualize them both. Here is the advent of God on the scene of nature. It is then that the model is to be found represented by the corresponding copy in nature.

God’s transcendental form also finds its corresponding reflection in nature, and when we worship the Deity in pure love, in the reflected scenes of Vrindavan. Here the imagination has no play. It is the soul which sees and makes a description in the corresponding phenomena in nature. The spiritual form thus conveyed to us is none but the eternal form of God. The grossness is simply apparent, but all the actions and consequences are fully spiritual.

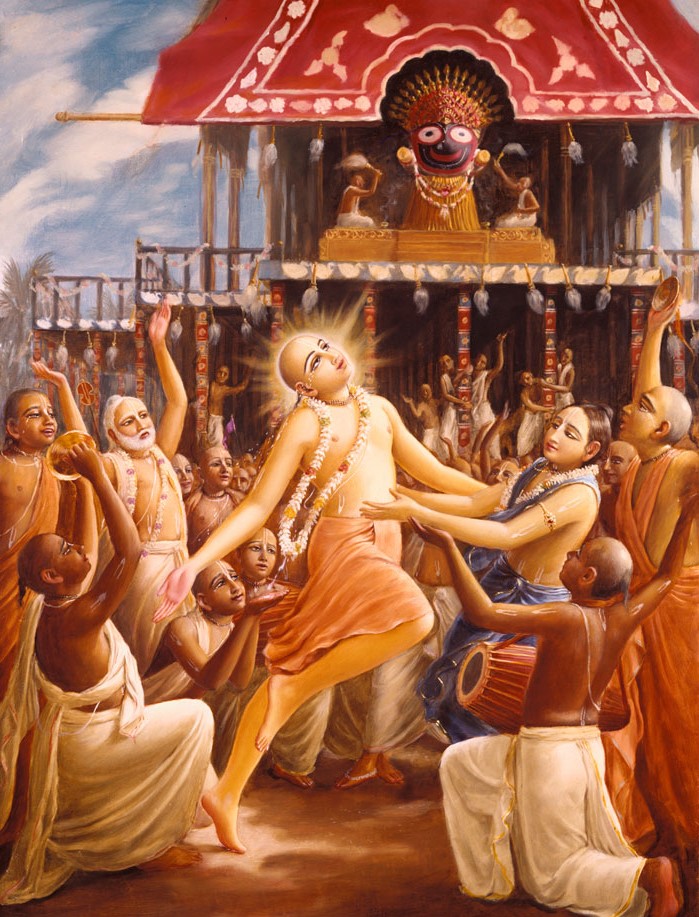

The man who weeps and dances in felicity when he spiritually sees the beauty of God is certainly translated to the region of spirits for the time and the gross action of his body is but a concomitant manifestation caused by a current of spiritual electricity. Here we find the absolute in the relative, the positive in the negative and spirit in matter. The spiritual form of God is therefore an eternal truth and with all its inward variety, it is one Undivided Unity. What appears to be a contradiction to reason is nothing but the rule of spirit. And the greatest surprise arises when we see full harmony in all these contradictions.

In 1884 the Thakur was transferred to Srirampur, near Saptagram, where he lived in a residence beside the court. His sons Radhika, Kamal and Bimal Prasad (Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati) stayed with him at this time. In October 1884 his mother died, and he performed the sraddha ceremony at Gaya. In 1885 the Thakur organized a press at Bhakti Bhavan, his residence in Calcutta. The press was called Chaitanya Yantra, or Chaitanya Press. From this time, the Sajjana-tosani was published, though not on a regular basis until after 1892.

In 1886 the Thakur was extremely prolific in writing and publishing Vaisnava literatures. He published his Bhagavad gita with commentaries, and Chaitanya-siksamrta, a work in Bengali prose based on Lord Chaitanya’s teachings to Rupa and Sanatan Goswami as found in the Caitanya-caritamrta. This book was very well received. He also published Sammodana-bhasyam, a Sanskrit commentary on Lord Chaitanya’s Siksastakam, the Bhajana-darpana-bhasya, a Bengali commentary on Srila Raghunath Das Goswami’s Manah-siksa, together with a Bengali verse translation of the Goswami’s Sanskrit poem.

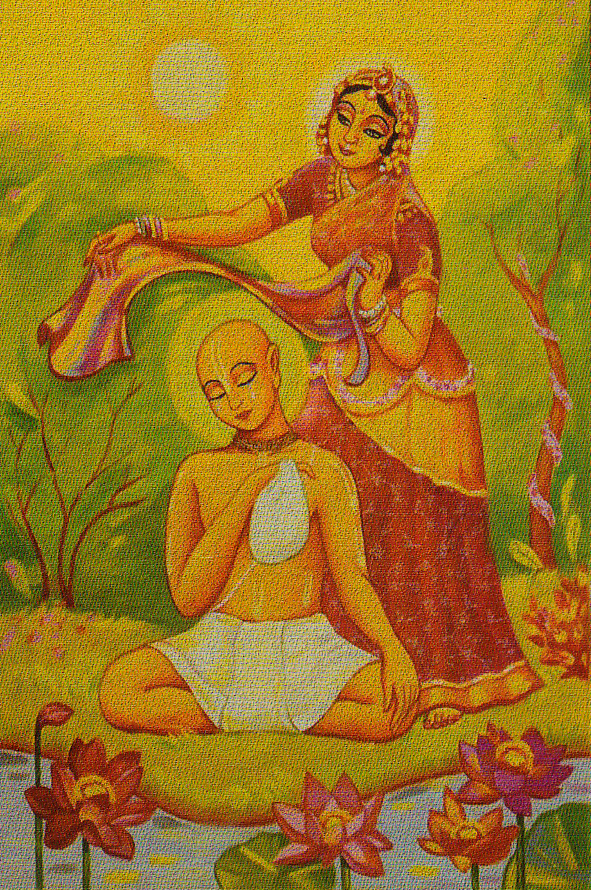

Raghunath Das Goswami being sheltered by Srimati Radharani

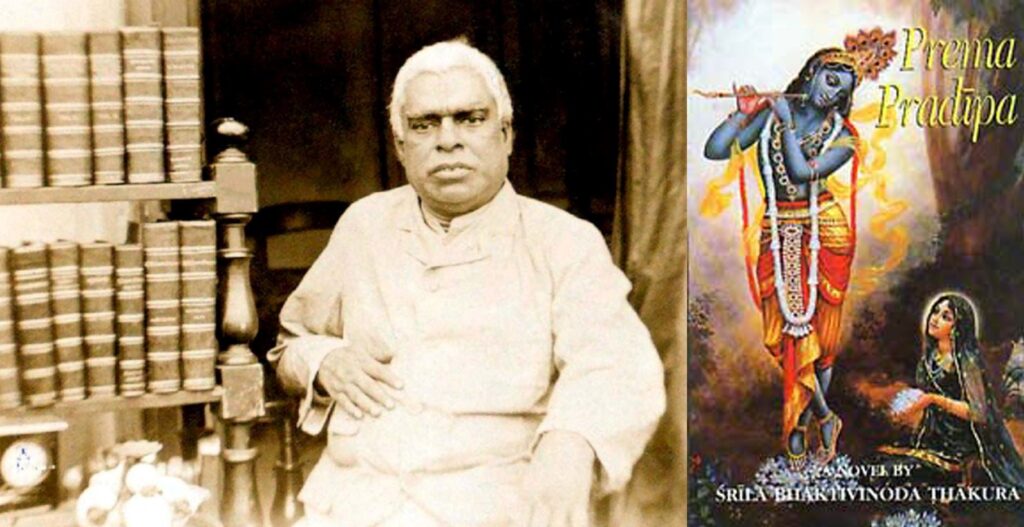

The Thakur also wrote Dasopanisad-curnika, a book of Bengali prose on the ten principal Upanishads, in1886. The Bhavavali, a compilation of Sanskrit verses by various Gaudiya Vaishnava acharyas on the subject of “rasa,” the different flavours of relationship experienced between Krishna and his liberated devotees in the spiritual realm, was also published at this time. The Thakur edited this work and provided Bengali translations of the verses. He also managed to write a philosophical novel called Prema-pradipa in Bengali prose, and to publish the Sri Vishnu-sahasra-nama from the Mahabharata with the Sanskrit commentary of Srila Baladeva Vidyabhusana, called Namartha-sudha.

Also in 1886, the Thakur established the Sri Visva Vaishnava Sabha, a spiritual society, in Calcutta, and many educated men became followers. Some of the meetings were held in Sarkar’s Lane and several committees were formed for the purpose of spreading Lord Chaitanya’s mission. The aims of the Society were expressed in a small booklet published by the Thakur, called the Visva-vaisnavi-kalpatavi.

The Thakur regularly lectured and read from the literature of the Goswamis at the Bhakti Bhavan, and his son Bimal Prasad (Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati) often attended, imbibing the Gaudiya Vaishnava philosophy from his father and also learning about the printing being carried out there.

The Thakur began work on an edition of Sri Caitanya-caritamrta with his own commentary called Amrta-prabhava-bhasya. Describing this period in his autobiography, the Thakur notes:

It was a highly intellectual task for me to publish all these books … Haradhan Datta of Badanganga came to Srirampur and offered a very old manuscript of ‘Sri Krishna-vijaya.’ I published that. At that time I established the Chaitanya Press, which was operated by Sri Yuktir Prabhu. When I had printed two khandas of the book Caitanya-caritamrta … I got a very intense head ailment from all this intellectual work.

For some time the Thakur could not work due to dizziness. At the suggestion of some Vaisnavas, he smeared ghee on his head, taking their instruction to be the suggestion of Srila Jiva Goswami, as he had, simultaneous to their urging, receved some of Jiva Goswami’s books.

Srila Jiva Goswami

I prayed to Srila Jiva Goswami that the affliction would not continue. Praying in this vein and applying ghee, my ailment vanished. Again I began to work and read the books [of the Goswamis].

In 1887, the Thakur travelled to many places in Bengal in search of the Caitanyopanisad, which is part of the Atharva Veda, but found only in very old manuscripts. Few people had even heard of this work, which offered overwhelming evidence of Lord Chaitanya’s identity as the Supreme Lord and yuga-avatara (for the present age of Kali Yuga). His endeavour was finally brought to the attention of Madhusudan Das, a Vaisnava pandit, who possessed an ancient manuscript of the Atharva Veda.

The pandit at once dispatched it to the Thakur from his place in Sambalapur. When the Vaishnava community learned of the Thakur’s discovery, they immediately requested him to prepare a Sanskrit commentary. The Thakur agreed and produced Sri Caitanya-caranamrta. Madhusudan Das assisted by writing a Bengali translation of the verses called Amrta-bindu.

The Thakur was awarded the title Bhaktivinoda during this period of his colossal efforts in preaching and book publication. The Thakur commented:

The masters had given the title Bhaktivinoda to me, and this was also the desire of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu …

The title “Bhaktivinoda” means “the pastime” or “the pleasure of devotional service.” Both meanings were appropriate, for the Thakur was the embodiment of one who performs and takes pleasure in the pastimes of devotional service. Combined with his earlier title of “Sac-cid-ananda,” from this time on the Thakur became known in the Vaishnava community as Sac-cid-ananda Bhaktivinoda Thakur.

Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur also began to propagate the Caitanya Panjika, a Vaisnava almanac (calendar) and it was by his efforts that the appearance day of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu was made a respectfully observed and important fast-day in the Gaudiya Vaisnava calendar. Around this time, Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur gave numerous lectures to various societies in Calcutta and other towns. He also published a detailed account of Lord Chaitanya’s life in the Hindu Herald, an English periodical, which was widely read and drew much favorable attention.

Leave A Reply