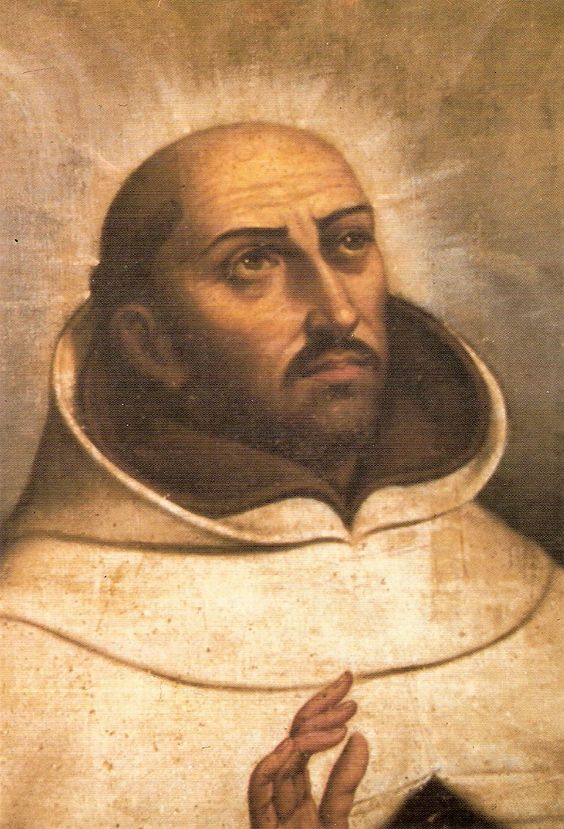

St. John of the Cross [San Juan de la Cruz] was born in 1542 at Fontiveros, near Avila, in the Kingdom of Castile in Spain. His father died in 1545, and his brother Luis died two years later. John’s mother struggled to support John and a surviving brother, Francesco, while working as a poorly paid weaver. From the age of ten until he was fourteen or fifteen, John was boarded at an orphanage school for poor children in Medina. Here he received a basic education, mainly in Christian doctrine, as well as food, clothing, and lodging.

After leaving the orphanage school around 1557, he worked for two years in a hospital, caring for patients who suffered from incurable diseases and madness. John studied the humanities at a Jesuit school from 1559 to 1563, before becoming a friar of the Carmelite Order in 1563. He then entered Salamanca University in 1564 for a three years’ course in Arts, studying under Fray Luis de Leon, a foremost expert in Biblical Studies who had written an important and controversial translation of the Song of Songs into Spanish – at a time when translation of the Bible into the vernacular was not allowed in Spain.

John’s life coincided with the time of the Spanish Inquisition, when much intrigue, torture and cruelty occurred within the Catholic Church in Spain. The Spanish Inquisition was a tribunal established in 1481 by Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile. It was intended to maintain Catholic orthodoxy in their kingdoms. The Inquisition was originally intended in large part to ensure the “orthodoxy” of those who converted from Judaism and Islam. Jews and Muslims were ordered to convert or leave Spain. In the Kingdom of Castile in 1481 six people were burned alive. From there, the Inquisition grew rapidly in Castile. By 1492, tribunals existed in eight Castilian cities. The body was under the direct control of the Spanish monarchy and amazingly was not abolished until 1834.

Pope Sixtus IV [1471-1484] stated of the Inquisition:

Many true and faithful Christians, because of the testimony of enemies … have been locked up in secular prisons, tortured and condemned … deprived of their goods and properties, and given over to the secular arm to be executed …

In 1567, after receiving his priest’s orders John met Saint Teresa of Avila, who convinced him to join the recently formed Discalced [“barefoot”] Reform – a breakaway chapter of the Carmelite Order of friars and nuns who practiced a much more renounced and austere lifestyle, reverting back to the “original rule” – the more austere practices of the original Carmelite order, which was formed in the early 1200’s.

Teresa was seeking to restore the purity of the Carmelite Order by restarting observance of its “Primitive Rule” of 1209, the observance of which had been relaxed gradually by a succession of mitigations awarded various popes. Being a reaction to the excesses and intemperance within Catholic Church of its day, many parallels could be drawn between the Discalced Carmelite Order in Spain and the Franciscan Order formed by St. Francis of Assisi in Italy, both of which were reform movements endeavoring to emulate the renunciation and poverty of Jesus and his original followers.

Saint Teresa of Avila

Under this Rule, much of the day and night was to be spent in study and devotional reading, the celebration of Mass and times of solitude and prayer. For the friars, time was to be spent evangelizing the population around the monastery. Total abstinence from meat and lengthy fasting was to be observed in the months leading up to Easter. There were to be long periods of silence, and coarser, simpler habits were to be worn. They were to follow the original injunction against the wearing of shoes, which was mitigated in 1432. It was from this last observance that the followers of Teresa among the Carmelites were becoming known as “discalced” or barefoot – differentiating themselves from the non-reformed friars and nuns.

After spending some time with Teresa, learning more about this new form of Carmelite life, in October 1568, John founded a new monastery for friars – the first for men following Teresa’s principles. At this time John adopted the name “John of the Cross.” In the early 1570’s, he founded a number of monastic communities. In 1572 he moved to Avila, where Teresa was prioress of the Monastery of the Visitation, becoming the spiritual director for Teresa and the other 130 nuns there, as well for as a wide range of laypeople in the city. John seems to have remained in Avila until1577.

The years 1575-77 saw great tensions among Spanish Carmelite friars over the reforms of Teresa and John of the Cross. Since 1566, the reforms had been overseen by Canonical Visitors who were meant to balance the interests of the Discalced Carmelites against those of the friars and nuns who did not desire reform. However, grave troubles arose between the Discalced and Mitigated Carmelite orders. The old friars looked upon this reformation, though it was undertaken with the approval of the Prior General, to be a rebellion against their order. The tension was fueled by confusing and contradictory policies being advocated and pursued by various authority figures within the church.

A General Chapter meeting of leaders of the Carmelite Order was convened in Italy in 1576, out of concern that events in Spain were getting out of hand. They ordered the total suppression of the Discalced houses. This measure was not immediately enforced, as King Philip II of Spain was supportive of Teresa’s reforms, and so was not immediately willing to grant the necessary permission to enforce this ordinance. Moreover the Discalced friars also found support from the papal nuncio, the representative of the Pope to King Philip II, and the Bishop of Padua, who still had ultimate power as Spanish nuncio to visit and reform religious Orders.

However, in 1577, while still in Avila, John was ordered to return to his original friary in Medina. He refused, on the ground that he held his office from the papal nuncio and not from the Carmelite order. In December of 1577, armed men broke into his dwelling and captured him. He was flogged twice before being removed in great secrecy to the Carmelite Monastery in Toledo. He was blindfolded and led into the city at night, so that he would not know where he was. At this time the Toledo Carmelite priory was the Order’s most important monastery in Castile, where perhaps 40 friars lived.

By the order of Jerome Tostado, who was the vicar general of the Carmelites in Spain, as well as a consultor for the Spanish Inquisition, John was pressed to abandon the name and distinctive dress of the Discalced Carmelite order, and to cease taking in novices or forming a separate order. They repeated the command to return to his priory at Medina. By refusing to comply he was accused of gross disobedience to a superior – considered the worst crime a prior could be guilty of. He was told his offence would be overlooked if he submitted now, and that he would be offered a high office in the order with a good cell and a library, and a gold crucifix.

In his reply, John said that though he venerated the orders of the vicar-general, he was neither obliged nor permitted to obey them because he had received an express order from the papal nuncio who was his immediate superior, not to do so. Further, he said that he had made a sacred vow to follow the original or “primitive” rule of the Carmelite Order, and was not free to break it. As for the punishment they threatened him with, he said he welcomed it, and it was precisely to avoid comforts and honors that he had joined the Discalced Order. He was found guilty of rebellion and insubordination, and by the order of vicar general Tostado he was condemned to imprisonment and bloodily beaten.

John was locked in a cell six feet by ten feet which was normally used as a toilet for the adjoining guest chamber. It was lit by a loop-hole three fingers wide and set high in the wall, so that to read he had to stand on a bench and hold up his book to the light, only being able to make out the print at midday. He could hear the Tagus River running in a deep ravine below. His bed was a board laid on the floor and covered with two old rugs, so that as the temperature of Toledo sank to below freezing point in winter and a damp chill struck through the stone walls, he suffered greatly from the cold. Later, as summer came around, he suffered equally from the heat of his stifling cell. He was given no change of clothes and was devoured by lice.

[The Spanish painter El Greco’s View of Toledo, 1575 depicts the priory in which John was held captive, just below the old alcazar (fort) and perched on the banks of the Tagus River on high cliffs. The alcazar is the tallest building to the right of the picture. The priory is the large building just below. El Greco and John of the Cross were nearly the same age, and El Greco lived in Toledo at very time of Saint John of the Cross’ imprisonment.]

This is a view of Toledo today. The alcazar is the large building on top of the hill. The priory where John was held captive is no longer there, but was just below the alcazar to the right.

John’s food consisted of scraps of bread and a few sardines – sometimes only half a sardine. These gave him dysentery and he wondered whether the monks were trying to poison him. On fast days, he was taken out of his cell to the dining hall where the friars sat at a large table. Forced to kneel in the center of the room, he was given his dry bread and water like a dog. Then he would be rebuked and criticized by the prior, who would accuse him of sowing discord among the friars, and of self-aggrandizement – aiming to be seen as a saint by others for the satisfaction of his own self esteem.

At these times, he would be given the circular discipline on his bare shoulders, with each of the friars striking him in turn with a cane while scripture was recited. This was the severest and most degrading punishment that could be given to a friar. John bore these scourgings in silence, displaying great tolerance. The younger friars pitied him, exclaiming, “Say what they like, he is a saint!” This caused the older friars to become even angrier. Claiming that his submissiveness was simply false humility, they called him a “sly boots” and a “snake in the grass.” The wounds he received did not heal properly for years, and he bore the scars of these beatings until the end of his life.

From his cell, John could sometimes hear the friars talking in the guest room next door. They spoke of the suppression of the Discalced houses, and falsely said that Teresa was in prison awaiting trial for heresy. He heard one friar say, “What are we keeping this man for? Let’s throw him in a well and finish with him.” Other voices said he would never leave the prison except to be buried. This seemed very likely, as he grew weaker every day – his dysentery grew worse and the suspicion kept returning that they were slowly poisoning him, and he would never leave his cell.

During his imprisonment John had no communication with anyone. His jailor was forbidden to speak to him and looked at him with hatred, opening his door only to throw his food upon the floor. His waste bucket was left for days without emptying it, so that the stench that came from it made him vomit. John came to look forward to his beatings in the refectory because on these occasions the prior spoke to him, though always in an angry and contemptuous manner. As the warm weather drew on, he began to suffer in other ways. His tunic, which was clotted with blood from his beatings, stuck to his back and putrefied. Worms bred in it so that his whole body became intolerable to him. He could no longer sleep or eat and felt that he only had death to look forward to.

After six months imprisonment a new jailor was appointed, a young man from another priory who took pity on him and gave him a clean tunic. He also gave him a pen and ink. One evening when he was in very low spirits, John heard a young man’s voice singing a love song in the street outside. The words were:

I am dying of love, dearest. What shall I do? – Die.

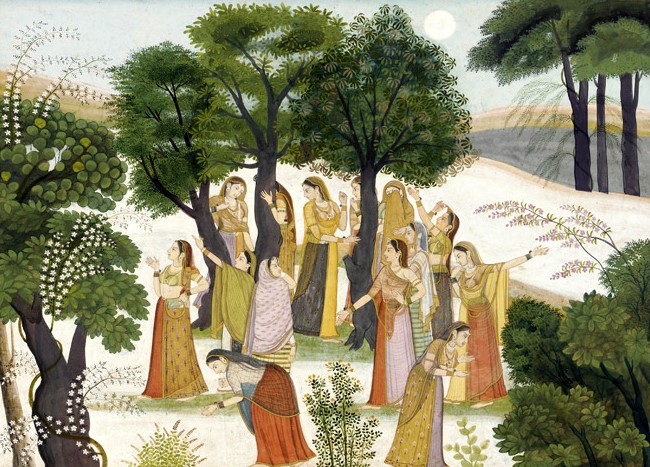

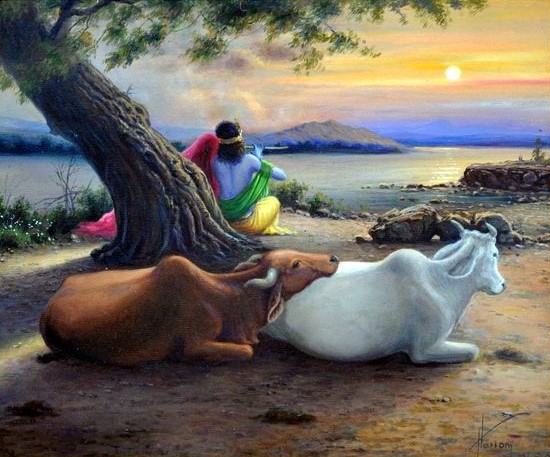

At once he was carried away in ecstatic trance. His experience inspired him to write his poem “The Spiritual Canticle,” part of which was composed in the prison at Toledo Priory. This poem is similar in nature to Solomon’s “Song of Songs,” from the Old Testament, and seems to refer to loving Krishna in the mood of the gopis, the cowherd maidens of Vrindavan.

The Spiritual Canticle

Where have You hidden, Beloved, and left me moaning?

You fled like the stag after wounding me.

I went out calling You, and You were gone.

Shepherds, you that go up through the sheepfolds to the hill,

If by chance you see Him I love the most,

Tell Him that I sicken, suffer and die.

Seeking my Love, I will head for the mountains and watersides,

I will not gather flowers, nor fear wild beasts.

I will go beyond strong men and frontiers.

O woods and thickets, planted by the hand of my Beloved,

O green meadow, coated bright with flowers,

Tell me, has He passed you?

Pouring out a thousand graces,

He passed these groves in haste,

And having looked at them, with His image alone,

Clothed them in beauty

Ah, who has the power to heal me?

Now fully surrender Yourself!

Do not send me any more messengers,

They cannot tell me what I must hear.

All who are free tell me a thousand graceful things about You,

All wound me more and leave me dying

Of, ah, I-don’t-know-what behind their stammering.

How do you endure, O life, not living where you live?

And being brought near death by the arrows you received

From that you conceive of your Beloved.

Why, since You wounded this heart, don’t You heal it?

And why, since You stole it from me, do You leave it so,

And fail to carry off what you have stolen?

Extinguish these miseries,

Since no one else can stamp them out.

And may my eyes behold You, because You are their light,

And I would open them to You alone.

Reveal Your presence,

And may the vision of Your beauty be my death

For the sickness of love is not cured,

Except by Your presence and image.

O spring like crystal! If only on your silvered-over [mirrored] face,

You would suddenly form the eyes that I have desired,

Which I bear sketched deep within my heart.

Withdraw them, Beloved, I am taking flight!

Return, dove,

The wounded stag is in sight on the hill,

Cooled by the breeze of your flight

My Beloved is the mountains, and lonely wooded valleys,

Strange islands, and resounding rivers,

The whistling of love-stirring breezes,

The tranquil night at the time of the rising dawn,

Silent music, sounding solitude,

The supper that refreshes, and deepens love

Be still, deadening north wind; south wind come,

You that waken love, breathe through my garden

Let its fragrance flow,

And the Beloved will feed amid the flowers.

Hide Yourself, my Love.

Turn Your face towards the mountains,

And do not speak, but look at those companions,

Going with her through strange islands

Swift-winged birds, lions, stags, and leaping roes,

Mountains, lowlands, and riverbanks,

Waters, winds, and burning fire,

Watching fears of night:

By the pleasant lyres and the siren’s song, I conjure you

To cease your anger and not touch the wall,

That the bride may sleep in deeper peace.

The bride has entered the sweet garden of her desire,

And she rests in delight, laying her neck

On the gentle arms of her Beloved

Following Your footprints, maidens run along the way.

The touch of a spark, the spiced wine, cause flowerings in them

From the ointment of God

In the inner wine cellar I drank of my Beloved

And when I went abroad through all this valley,

I no longer knew anything, and lost the herd I was following.

There He gave me His breast;

There He taught me a sweet and living knowledge.

And I gave myself to Him, keeping nothing back.

There I promised to be His bride.

Now I occupy my soul and all my energy in His service.

I no longer tend the herd, nor have I any other work,

Now that my every act is love

If, then, I am no longer seen or found on village ground,

You will say that I am lost, that stricken by love,

I lost myself and was found.

With flowers and emeralds chosen on cool mornings,

We shall weave garlands flowering in Your love,

And bound with one hair of mine

You considered that one hair fluttering at my neck:

You gazed at it upon my neck and it captivated You,

And one of my eyes wounded You.

When You looked at me, Your eyes imprinted Your grace in me.

For this, You loved me ardently, and thus my eyes deserved

To adore what they beheld in You.

Let us rejoice, Beloved,

And let us go forth to behold ourselves in Your beauty,

To the mountain and to the hill, to where the pure water flows;

And further, deep into the thicket.

And then we will go on to the high caverns in the rock,

Which are so well concealed.

There, we shall enter and taste

The fresh juice of the pomegranates.

There, You will show me what my soul has been seeking.

And then You will give me, You, my life, will give me there,

What You gave me on that other day:

The breathing of the air,

The song of the sweetest nightingale,

The grove and its living beauty in the serene night,

With a flame that is consuming and painless.

[Excerpts from “The Spiritual Canticle”]

Later, when Saint John managed to escape from prison, and take refuge with the Carmelite nuns of Toledo, he shared with them his poems. The beauty and subtlety of his poetry deeply impressed them. The nun entrusted with making copies of the poems, asked John if God gave him the words. He responded, “Daughter, sometimes God gave them to me, and at other times I sought them myself.” When asked if any consolation had been given in prison, he replied, “My daughter Ana, one single grace of those that God gave me could not be paid for by many years in prison.” “Do not be surprised,” he also said in later years, “if I show a great love of suffering. God gave me a high idea of its value when I was in prison in Toledo.”

August came and the heat in his airless cell grew stifling. John felt that if he remained in it much longer he would reach a point of no recovery. His new jailor began leaving the cell door open while the friars took their siesta, and John started emptying his bucket at this time, and was able to explore part of the building where he was confined. The Carmelite priory was a huge stone building that rose ninety feet above the rocky bed of the Tagus River. He had been held captive there for nine months.

Alcantara Bridge existed during John’s imprisonment at Toledo. The alcazar (old fort) can be seen with its two pointed turrets. This is the site of the priory where John was imprisoned.

The jailor gave John a needle, thread and scissors to mend his habit. He also gave John an oil lamp to read by. At one time, while the friars slept, John attached the thread to a small stone and dangled it out of a window until it reached the ground below. This enabled him to calculate that if he cut up his two rugs into strips and tied them together, they would reach within ten feet of the ground below. Every afternoon while his cell was open, he worked on loosening the latch on his door, so that it would open if he gave it a strong push.

One night John cut his two rugs into strips by the light of the oil lamp. Two visiting friars who arrived that day were lodged in the guest room off his cell. Though this made his escape from his cell more difficult, it meant that the door to the gallery was left open to give the guests more fresh air. At two o’clock in the morning, John guessed that they would be fast asleep. A voice in his head said, “Be quick, be quick,” and he took the lamp and rope and pushed the door open. The lock fell to the floor with a loud crash and the friars awoke and enquired “What is that?” Finally they fell asleep again, and John passed between their beds and moved out into the gallery.

The Tagus River at Toledo

A full moon was shining, lighting up the steep slope beyond the river with its rocks and gnarled olive trees, throwing the yard below into deep shadow. He slipped the blanket rope over the edge, took off his habit and threw it over the edge, and then slid down the rope until the end, letting himself fall the remaining distance. He landed on a pile of stones at the foot of the city wall, within just a couple of feet of a sheer drop to the rocks of the Tagus. He could hear the river gushing through its narrow gorge below.

He put on his habit and scrambled along the top of the city wall until he found a place where a pile of rubble enabled him to descend to the ground. He realized he was now in the walled courtyard of the adjoining convent for Franciscan nuns, with a bolted door and no way out. Despair overcame him. When morning came he would be discovered within the confines of an enclosed convent, a cause of scandal for the entire city. He contemplated calling out to the Carmelite friars from whom he had escaped, but decided to make one last effort to reach freedom.

Then, according to one account, he saw a dog looking for food scraps tossed from the refectory [dining room] window. In order to find out how it got into the yard, he threatened it and it ran to a part of the wall and disappeared. Following the dog, he found a junction between two walls where plaster had come out to leave footholds. He somehow managed to climb it despite his feeble condition, then dropped down to the other side. He spent the remainder of the night in the entrance hall of an obliging caballero’s [gentleman’s] house, and next morning he was able to find his way to a convent of Discalced Carmelite nuns in Toledo, who hid him, gave him food and gathered around to hear his exciting story.

One nun later said that he was so weak, thin and disfigured from hunger that he looked like death. After being nursed back to health by Teresa’s nuns in Toledo, and then during six weeks at the Hospital of Santa Cruz, John continued with reform. In October 1578 he joined a meeting of the supporters of reform, increasingly known as the Discalced Carmelites. There, in part as a result of the opposition faced from other Carmelites in recent years, they decided to demand from the Pope their formal separation from the rest of the Carmelite Order.

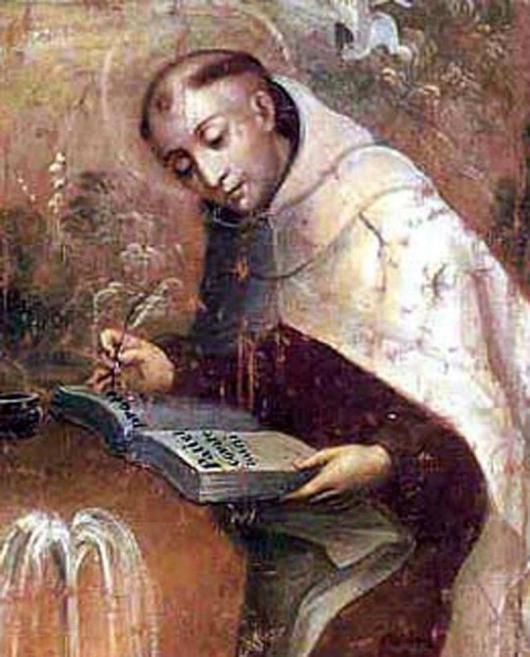

John was appointed superior of El Calvario, an isolated monastery of around thirty friars in the mountains about 6 miles from Beas in Andalucia. While at El Calvario he composed his first version of his commentary on his poem, The Spiritual Canticle. In 1579 he moved to Baeza, a town of around 50,000 people, to serve as rector of a new college, the Colegio de San Basilio, to support the studies of Discalced friars in Andalucia. This opened in June 1579. He remained in post there until 1582, spending much of his time as a spiritual director for the friars and townspeople.

1580 was an important year in the resolution of the disputes within the Carmelites. In June that year, Pope Gregory XIII signed a decree which authorized a separation between the Calced and Discalced Carmelites. At the first General Chapter [meeting] of the Discalced Carmelites in 1581, John of the Cross was elected one of the “Definitors” of the community, and wrote a set of constitutions for them. By 1581 there were 22 houses, some 300 friars and 200 nuns in the Discalced Carmelites.

In 1585, John travelled to Malaga and established a monastery of Discalced nuns there. In May that year, at the General Chapter of the Discalced Carmelites in Lisbon, John was elected Provincial Vicar of Andalusia, a post which required him to travel frequently, making annual visitations of the houses of friars and nuns in Andalusia. During this time he founded seven new monasteries in the region, and is estimated to have travelled around 25,000 km.

In 1588, he was elected third Councilor to the Vicar General for the Discalced Carmelites, Father Nicolas Doria. After disagreeing in 1590-1 with some of Doria’s remodeling of the leadership of the Discalced Carmelite Order, John was removed from his post in Segovia, and sent by Doria to an isolated monastery in Andalusia called La Penuela. The priory of La Penuela was an old abandoned hermitage that had been resettled. It stood on a small plain, surrounded by evergreen oaks and cistus heath on the lower slopes of the Sierra Morena. In John’s time it was the loneliest and most isolated of all the Discalced houses.

Sierra Moreno Ranges in Andalusia

The prior at La Penuela had once been one of John’s novices, and he appointed him spiritual director of the community, but otherwise assigned him no duties. For this reason John seems to have been happier there than he had been for years. He wrote in a letter that “the vastness of the heath helped both body and soul. This morning we have been picking our chick peas and will be picking them all this week. Then we shall shell them. It is pleasant to handle inanimate creatures – far pleasanter than being ourselves handled by living ones.”

His custom at this time was to rise before dawn and kneel in prayer under some willow trees by a running stream, where he would remain until the heat of the day drove him in. The priory was surrounded by an orchard, an olive plantation of three thousand trees, a vineyard and a hundred and fifty acres of arable land on which the friars grew corn. Sometimes he would ask permission to go beyond its limits – as far as the wild scrub of cistus, terebinth, arbutus and giant heather that covered the surrounding hills.

Then once a week he would set off for Linares to preach in the church there, making the journey of fifteen miles each way while fasting or, if he was feeling unwell, stopping to eat some bread and watercress by a stream. At night he slept on a mat woven of rosemary and broom, but much of the time that was allotted for sleep he devoted to prayer. As usual, he spent much of his free time in writing, composing a second version of his prose work, “The Living Flame of Love,” which describes John’s growing relationship with the Lord in the heart:

The Living Flame of Love

O living flame of love,

How tenderly You wound

And sear my soul’s most inward centre!

No longer so elusive,

Now, if You will conclude

And rend the veil from this most sweet encounter.

O cautery that heals!

O consummating wound!

O soothing hand!

O touch so fine and light

That savours eternity

And satisfies all dues!

Slaying, You have converted death to life.

O lamps of burning fire

In whose translucent glow

The mind’s profoundest caverns

Shine with splendour

Before in blindness and obscure,

With unearthly beauty now

Regale (delight) their love

With heat and light together.

With what love and sweetness

You waken in my breast

Where in secrecy and solitude You move:

Suffused with joy and goodness

In the fragrance of Your breath,

How delicately You kindle me with love!

St John also spoke of spending time in solitude with the Lord in the Heart in the following passage from The Spiritual Canticle:

God is hidden in the soul. You yourself are His dwelling and His secret chamber and hiding place. God is never absent. In order to find Him you should forget all your possessions and all creatures and hide in the interior, secret chamber of your spirit. And there, closing the door behind you, you should pray to your Father in secret. Remaining hidden with Him, you will experience Him in hiding and love and enjoy Him in hiding.

Another poem of St. John of the Cross which seems very likely to be addressing the loving pastimes of Krishna and the gopis is “The Dark Night.”

One dark night,

Fired with love’s urgent longings

(Ah, the sheer grace!)

I went out unseen,

My house being now stilled

In darkness, and secure,

By the secret ladder, disguised,

(Ah, the sheer grace!)

In darkness and concealment,

My house being now all stilled.

On that glad night,

In secret, for no one saw me,

Nor did I look at anything,

With no other light or guide

Than the one that burned in my heart.

This guided me

More surely than the light of noon

To where He waited for me

(Him I knew so well)

In a place where no one else appeared

O guiding night!

O night more lovely than the dawn!

O night that has united

The lover with her Beloved,

Transforming the lover in the Beloved

Upon my flowering breast

Which I kept for Him alone,

There He lay sleeping,

And I caressing Him there

In a breeze from the fanning cedars

When the breeze blew from the turret

Parting His hair,

He wounded my neck

With His gentle hand,

Suspending all my senses

I abandoned and forgot myself.

Laying my face on my Beloved,

All things ceased.

I went out from myself, leaving my cares

Forgotten among the lilies

If these poems were not written in the mood of conjugal love of God, then it would be exceedingly strange for such a renounced celibate monk to write what would appear to be mundane love poems, and then share them with nuns. And then for them to become treasures of Spanish mystical religious literature.

The last years of St. John of the Cross’ life were full of reported “miracles,” witnessed by those who were close to him. At Segovia bright lights were observed coming out of his cell, and aromatic odours hung about his confession box. While praying in the garden he would be lifted a few inches into the air. He impressed everyone about him as being a saint. It was said that at La Penuela he stopped a field fire that was on the point of burning down the priory by kneeling in front of it. However, the only supernatural event that John actually admitted to in connection to himself took place at Segovia, when the figure of Christ in a painting addressed him as he was praying before it. However, as the author Gerard Brennan rightly pointed out:

The real miracle lies in his life of constant absorption in God to the exclusion of all else.

[Gerard Brennan: “St. John of the Cross, His Life and Poetry.”]

It seems that many of John’s letters and much of his writing was destroyed, perhaps by officers of the Inquisition, as there is evidence that he was on a number of occasions under the scrutiny of their investigators and came close to being arrested on at least one occasion. This was according to Juan Antonio Llorente, who had at one stage been an Inquisitor of the Inquisition before becoming an historian of the institution and writing a book on the subject in 1822. John’s life of poverty and persecution could have produced a bitter cynic. Instead it gave birth to a compassionate servant of God, who lived by the beliefs that:

Where there is no love, put love – and you will find love.

The Passing of St John of the Cross

In 1591, Saint John of the Cross was struck down with a fever, which came from an inflammation on his right foot. In order to get medical treatment, he travelled from La Penuela to a priory at Ubeda. The prior there was a harsh and rigid man who felt a special dislike for those who were regarded by others as saints. He therefore gave him the smallest and poorest cell in the building and one day, when John felt too sick to drag himself to the refectory (dining hall), he sent for him and reprimanded him harshly in front of the other friars.

In the meantime, John’s fever and inflammation were growing worse. A surgeon opened his foot with a knife and a large quantity of pus came out. Soon after this, the whole of his leg, which was very swollen, broke out into ulcers. The surgeon cut, probed and cauterised, causing the sick man intense pain which he bore with such patience and gentleness that the doctor who was attending him became convinced that he was a saint and preserved as relics the swabs that had been used on his sores and which he noticed smelt sweet and fragrant.

The women who washed his bandages, struck by the odour of musk they gave off, did the same and a belief in his saintliness spread through the town. Only the prior remained hostile. Irritated by the attention that was paid to the sick man, he complained that the house could not afford the food that the doctors prescribed, though most of the food John ate came from his friends. The prior would go to John every day, and stand by his bedside, scolding him for his faults.

The sick man continued to grow worse. Tumours broke out all over his body, the largest and most painful being on his shoulder. Since he could not bear to be touched, a rope was hung from the ceiling by which he could lift himself. As his suffering increased he would mutter, “More patience, more love, more pain.” Very soon it became clear that he was dying.

He asked to see the prior and begged his forgiveness for all the trouble he had given him. The man, struck by shame and remorse, apologised for not having attended to him better, making the face-saving excuse that the priory was very poor. “Father,” replied John, “I have been treated far better than I deserve. But do not let yourself be distressed by the poverty of the house for if you have faith in the Lord it will soon be relieved.” The prior left the cell weeping.

John was given last rites – the sacrament of the dying – after which he lay all day in great pain, unable to speak. Then at 11.30 P.M. he sat up in bed, his face flushed with happiness, and said, “How well I feel!” He asked the time and on being told it, said, “The hour is approaching. Call the Fathers.” The fourteen or so friars who were staying in the priory trooped into his cell, each of them carrying a small oil lamp which he hung on the wall. Standing at the foot of his bed in that tiny room they recited the De profundis (Psalm 130) and the Miserere (Psalm 51).

Out of the depths I cry to you, O Lord. O Lord, hear my voice. Let your ears be attentive to my cry for mercy. If You, O Lord, kept a record of sins, O Lord, who could stand? But with You, O Lord, is forgiveness. … I wait for the Lord, my soul waits for the Lord more than watchmen wait for the morning. … O Israel, put your hope in the Lord, for the Lord is unfailing love, and with Him is full redemption (forgiveness and protection) …

[Psalm 130]

Have mercy on me, O God, according to Your unfailing love. According to Your great compassion, blot out my transgressions. … Cleanse me with hyssop, and I will be clean. Wash me and I will be white as snow. Let me hear joy and gladness. Let the bones You have crushed rejoice. … Create in me a pure heart, O God, and renew a steadfast spirit within me. Do not cast me from Your presence or take Your Holy Spirit from me. … O Lord, open my lips, and my mouth will declare your praise. You do not delight in sacrifice, or I would bring it. You do not take pleasure in burnt offerings. The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit, a broken and contrite heart …

[Psalm 51]

Then the dying man asked one of them to read aloud some verses from the Song of Songs:

Let Him kiss me with kisses of His mouth! More delightful is Your love than wine. Bring me, O King, to Your chambers. O My Lover, here He comes across the mountains, across the hills. My lover is radiant and ruddy; He stands out among thousands. His head is golden, His locks are like palm fronds, black as a raven. His eyes are like doves beside running waters. His teeth would seem bathed in milk, and are set like jewels. His lips are red blossoms. His arms are rods of gold adorned with chrysolites. His body is a work of ivory covered with sapphires. His legs are columns of marble. His mouth is all sweetness itself; He is all delight. Such is My Lover, and such is My Friend.

[Old Testament: Song of Solomon]

“Oh, what exquisite pearls!” he murmured. The friars trooped out. The church clock struck midnight – the hour for matins [a Roman Catholic prayer recited at midnight]. “Tonight I shall sing matins in Heaven,” said John and, folding his arms in front of him, ceased to breathe. Saint John of the Cross died in 1591 at Ubeda in Spain. At some point John had written a very beautiful poem about dying in the mood of separation from the Lord:

Dying Because I do not Die

Not living in myself I live

And wait with such expectancy:

I die because I do not die.

I live within myself no longer,

Deprived of God I cannot live.

Lacking Him and self I’m left.

So such a life – what will it be?

It will deal a thousand deaths to me

Since I await my very life,

Dying because I do not die.

This life I live in such a way

Is nothing but life’s deprivation,

One prolonged annihilation

Till at last I live with Thee.

Hear, my God, hear what I say,

I do not want this life of mine:

I die because I do not die.

Being absent and apart from Thee,

What kind of life can I possess?

But one that bears the pangs of death,

The worst of deaths I’ve ever seen

I have some pity for myself

Since by living I continue

To die because I do not die.

Even the fish drawn out of water

Does not lack alleviation,

Death comes at last, the termination

Of the death-throes that it suffers.

What death is there to equal

This sad, despairing life I live?

The more I live the more I die.

When thinking it will bring relief

To see Thee in the Sacrament

My pain and grief are only deepened

To find that I cannot enjoy Thee.

All brings me greater misery

Not to see Thee as I long to

And I die because I do not die.

And if I take delight, my Lord,

In hope of seeing Thee,

On seeing I can lose Thee

My agony is doubled.

Living in so great a dread

And waiting, yearning as I do,

I die because I do not die.

Lift me from this death, release me,

Give me living life, my God,

Not keep me in so strong a bond

To cripple and impede me;

For look, I long, I grieve to see Thee,

My sickness fills me so completely

That I die because I do not die.

I will mourn my death already,

Lament the life I live, as long

As misdeed, sin and wrong

Detain it in captivity.

O my God, when will it be?

The time when I can say for sure,

At last I live: I die no more.

St. John of the Cross’ poems are generally interpreted by scholars as being symbolic of the soul’s growing love for God:

… the Spiritual Canticle uses the allegory of the soul seeking the Bridegroom (God). “Where have you hidden, O my Beloved, and left me moaning?”

[Bede – Owlcation]

Sharon Mesmer, in her article “Silence and Contradiction” on the Commonweal website, reviews a new book on the poetry of Saint John of the Cross. In the article she says:

While the poetry of San Juan de la Cruz is admired by poets and lovers of poetry for its mystical beauty, it often gets the side-eye from religious. Thomas Moore, a one-time Carmelite himself and author of Care of the Soul, among other books, once wrote:

One of my Pastors once remarked to me, with a grimace that bordered on pain, “St. John of the Cross? I cannot get anything out of him. Even at the Seminary we said ‘What is it that he is saying?’ Is he saying anything at all to us?” Sadly, I must admit that I often meet people who display similar reactions. Why? What causes people to be so turned off by this saint, while others become so turned on?

The saint’s poems, written more than four hundred years ago and considered the apex of Spanish mystical literature, seem to forget the familiar, easy, and convenient, to slip into darkness and unknowing to find God. They are written in a highly symbolic, sometimes sensual language. It’s no wonder translators got it wrong.

[Sharon Mesmer: Commonweal website October 13, 2021]

However, I would suggest Saint John’s poems are meant very literally, and not properly understood by scholars who are lacking in knowledge of Krishna’s pastimes in the rasa or mood of conjugal love. At least in the poems I have quoted, John is speaking of his profound spiritual experiences. This is a totally different thing to writing allegorical stories to try and explain spiritual truths. And yet, they are still considered to be the summit of mystical Spanish literature and one of the peaks of all Spanish literature. The writer Bede says of St John’s poetry:

…it was through nine months of cruel imprisonment that the Carmelite mystic, St. John of the Cross, gave birth to arguably the finest poetry in the Spanish language.

[St. John of the Cross: A Poet in Prison: Owlcation August 17 2020]

Saint John of the Cross was canonized as a saint in 1726 by Pope Benedict XIII and is one of the thirty-five “Doctors of the Church.” Though we should not speculate on his experiences or advancement, much of his teachings seem very much in harmony with Vaisnava teachings, and he definitely taught bhakti – that love of God is the ultimate goal of life and the only means to attain God:

The will is content with nothing less than His presence and the sight of Him. This immensity is indescribable and because of it the soul is dying of love. The sickness of love is not cured except by Your very presence and image.

… it is love alone that unites and joins the soul with God.

Who has ever seen people persuaded to love God by harshness?

In the evening of life, we will be judged on love alone.

[Excerpts from: “St. John of the Cross, His Life and Poetry” – Gerard Brennan, 1973; other information from “Lives of the Saints,” “John of the Cross” – Wikipedia, “The Spanish Inquisition” – Wikipedia; “St John of the Cross: A Poet in Prison,” Owlcation August 17 2020; Sharon Mesmer: “Silence and Contradiction,” Commonweal website October 13, 2021]

Leave A Reply